View this Publication

Strengthening America’s Rural Innovation Infrastructure

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction:

Framing Questions and Motivation

Rural America has caught the nation’s attention. Our nation is full of questions about it. The media, voters, public officials, investors and neighbors are asking: “What is rural? What is happening there? Who lives there? Why? Why do they think the way they do? How are they doing? What can be done about it?”

“We know a lot about what works. It takes strong leadership and effective intermediaries to pull the paint from the palette and do the work over time.”

Justin Maxson, Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation

This report addresses questions often asked by caring people who shepherd resources that could be channeled to advance rural people and places — foundation leaders, individual investors and government officials. “We’d like to do more for rural America,” they offer. “But who can we work with? And besides that, what works?”

The research behind this report is motivated by a specific version of that “what works” question: “What actions could shift mindsets, construct or revise systems and policies, and build capacity to advance rural community and economic development in a way that improves equity, health and prosperity for future generations?”

Rural practitioners have answers to these questions. So we looked to them — combining fresh research with what the Aspen Institute Community Strategies Group (CSG) continues to learn from development practitioners through our work in rural America. Since 1985, CSG has helped connect, equip and inspire local leaders as they build more prosperous regions and advance those living on the economic margins. More than 75% of our work has been in rural America. We have worked with rural doers from nearly every state, both on the ground and at peer gatherings that we have organized to help leaders from different places learn from and advise each other. In turn, CSG has gleaned insight from the people doing the best work to build and rebuild our nation’s rural economies.

At the heart of any positive, inclusive community and economic development action in rural places are the efforts of rural and regional intermediary organizations. Intermediary is a fuzzy term to some, so we’ll define what we mean in our context: Intermediaries are place-based organizations that work to improve prosperity and well-being by harnessing local and outside resources to design and deliver services and products to people, firms and organizations in their region.

This report focuses on the role — and aggregates the wisdom — of a specific set of intermediaries that are doing development differently in rural America. We have chosen to call them Rural Development Hubs — or Hubs for short. We focus here on Rural Development Hubs because they are main players advancing an asset-based, wealth-building, approach to rural community and economic development in this country. They are the most visible actors in rural America designing and implementing efforts that simultaneously:

- Increase and improve the assets that are fundamental to current and future prosperity: individual, intellectual, social, cultural, built, natural, political and financial capital.

- Increase the local ownership and control of those assets.

- Always include low-income people, places and firms in the design of their efforts — and in the benefits.

In short, Hubs focus on all the critical ingredients in a region’s system that either advance or impede prosperity — the integrated range of social, economic, health and environmental conditions needed for people and places to thrive.

To produce our findings, we conducted interviews with the leaders of 43 Rural Development Hubs from across the country. The interviews were candid, rich, provocative and inspiring. The conversations dug into how these practitioners and their organizations approach their work — their strategy, values and relationships in the community — along with their roles, how their organizations have evolved by necessity over time, and what helps or hinders their progress.

“Our aim is to create a place at the table for all parts of the community, especially those parts that may look different or have not always been included in the conversation. Inclusion cannot happen on its own. It must be an intentional part of any economic or community development strategy.”

Patrick Woodie, NC Rural Center

One thing our interviews reinforced: Innovation is not confined to urban America.1 Rural Development Hubs are full of the creative adaptation and ingenuity critical to doing the hard work of rebuilding economies and communities for the 21st century. Rural Hubs are also full of ideas about how to do more and better for rural America. Their recommendations should help investors, policymakers and other decision makers who have questions about rural America.

In issuing this report, we also invite conversation — constructive critique that sharpens our findings. We welcome a lively exchange of ideas about how to produce better community and economic development results in rural America, including how to strengthen existing Hubs and nurture new ones. By itself, building more and stronger Rural Development Hubs cannot do the whole job. But our experience and this report’s findings indicate that Hubs are a critical piece of our nation’s rural development ecosystem. In short, strengthening the enabling environment for Rural Development Hubs is an essential component for building equity, health and inclusive wealth in rural America and strong, vibrant, 21st Century prosperity for our nation.

A Few Things to Know About Rural America

Knowing what is true about rural places and people is a challenge. Too often, people lump all of rural America into one “flyover-country” stereotype. But saying that all of rural America is the same is like saying Detroit and San Francisco are the same, or Birmingham and Boston. Here are a few truths worth knowing about rural America.

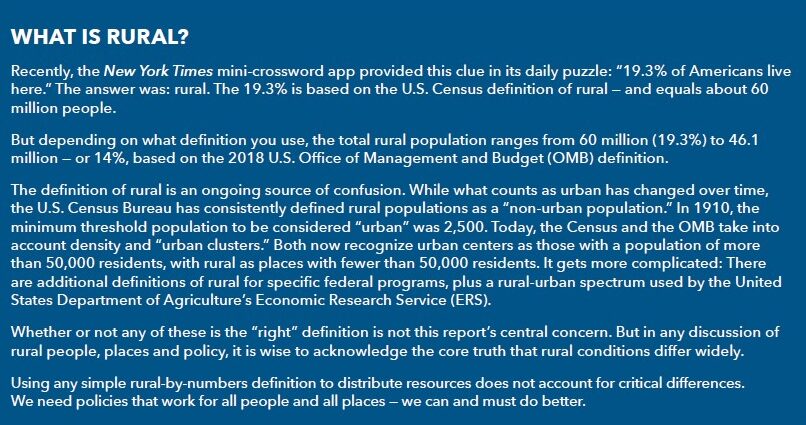

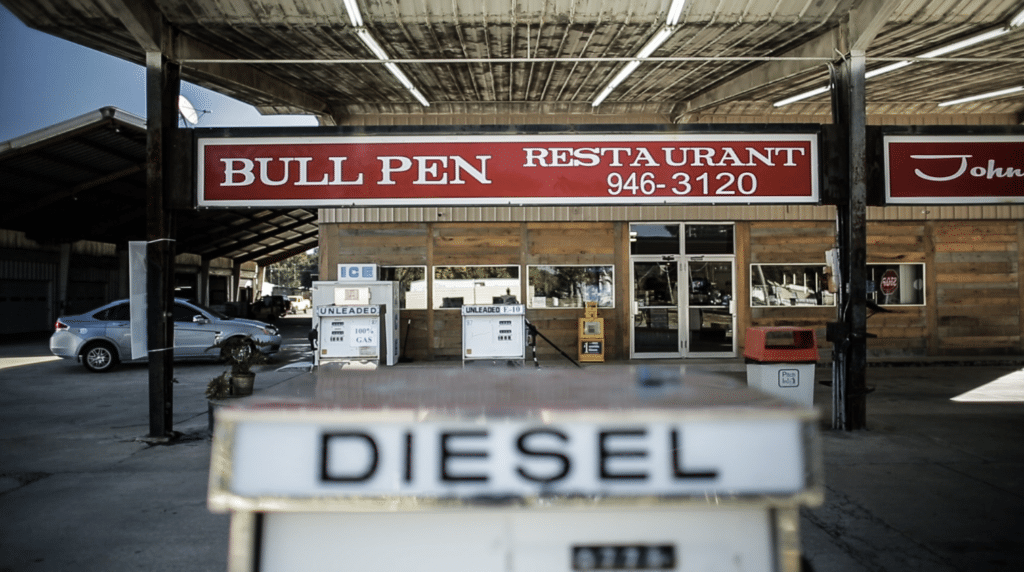

Rural America Varies Widely by Economic Base and Geography. Rural is typically defined — even in national data — as “non-metropolitan” or “non-urban.”2 This doesn’t tell us much. Perhaps due to this lack of precision and our nation’s agrarian roots, people still commonly equate rural with agriculture, fields of corn, cows and hardscrabble farmers. This is not only inaccurate; it is wide of the mark. From vibrant college towns to communities gone bust from the flight of paper mills or coal mines, from hopping cultural tourism locales to centers of furniture, machinery and textile manufacturing, rural America is anything but simply farmland, and it is anything but uniform. Rural New England, New Mexico, Montana, Louisiana and Kansas may share some similar conditions, but have strikingly different geographies, with differing economic engines and assets, populations, cultural values and origin stories.

Here’s one statistic that surprises most: While still economically and culturally important, agriculture now employs less than 5% of the rural workforce. Indeed, across rural America, it is services (professional, health, retail, social, tourism), manufacturing, energy and the public sector that are the primary employers and increasingly important drivers of rural economies.3

Rural America Is Growing, but Growth Is Uneven. The too-conventional wisdom, repeated in the media and coffee shops, is that rural America is emptying out. The truth is that the U.S. rural population has been fairly stable in recent years and has shown modest growth each of the last two years, from 2016-18.4 Another contributing factor to the mistaken “emptying” perception: Due to growth, many once-rural places have simply been reclassified as urban.5 And while the percentage of Americans who live in rural places has declined over time, the number of people living in rural America increased 11% from 1970- 2010.6 Indeed, about half of our nation’s roughly 2000 rural counties grew in population from 2016-18. This has coincided with declining rural unemployment, rising incomes and declining poverty since 2013.7

The rural places that are growing are typically those near metropolitan areas, those with abundant beauty and natural resources, those attracting retirees, and those employing immigrants. Some rural places are losing population, such as farming counties in the Great Plains and deeply poor counties in the South.8 But remarkably, every state in our union has both some growing and some declining rural counties.

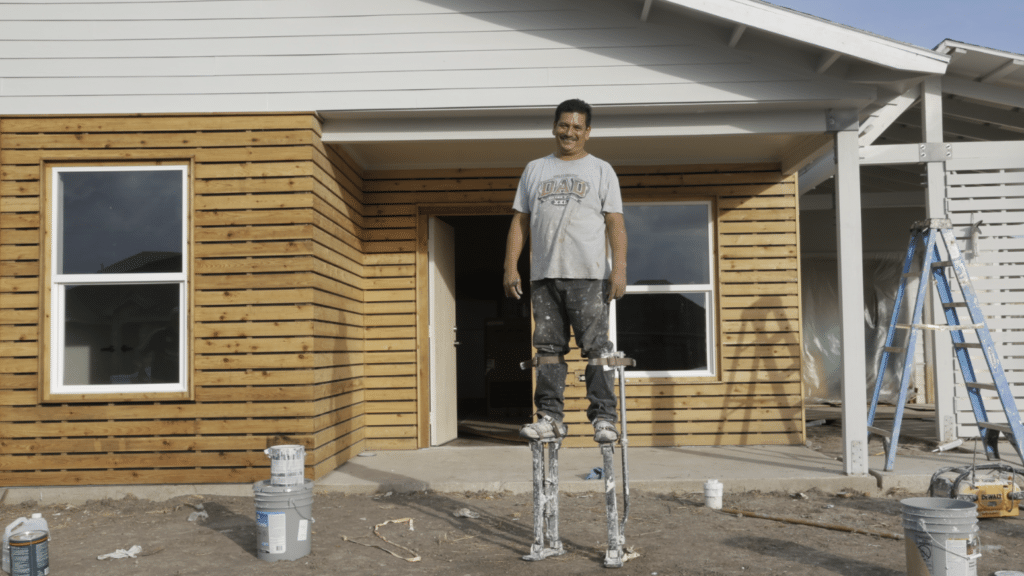

Like All of America, Rural America’s Population Profile is Changing. While consistently older and whiter than the nation as a whole, rural America is increasingly diverse. People of color comprise 21% of the rural population — but produced 83% of its growth between 2000 and 2010.9 Patterns vary across geographies, but job-seeking immigrants are a driving force behind recent rural population upturns: From 2010-2016, immigrants were responsible for 37% of overall rural population growth.10 Other analysis shows areas with a rural “brain gain” of people aged 30-49 and 50-6411 — age groups that tend to move rural for a simpler pace of life, safety, security and lower housing cost. In a nation where cities are increasingly crowded and costly, rural places offer an affordable and high-quality alternative. Some rural communities have even launched recruitment campaigns for these age groups — and are succeeding.12

Economic, Social and Health Outcomes Lag in Many Rural Places. The great variation from place to place in rural America includes economic, social and health outcomes, which, on average, lag those of urban places, sometimes alarmingly so. Much of this has to do with poverty. Since the 1960s, when poverty rates were first officially recorded, the incidence of non-metro (rural) poverty has been consistently higher relative to metro (urban) poverty. The difference has narrowed, but it remains. In 2017, the rural poverty rate stood at 16.4% compared to urban at 12.9%.13 For children, the rural poverty rate was 22.8%, more than five points higher than urban’s 17.7%.14 The good news: The number of rural counties ERS designates as “persistent poverty” — those with 20% or higher poverty for the previous four decennial census counts — has declined since the 1950s. The bad news: Most rural counties where severe poverty persists are found in the Mississippi Delta, Appalachia, northern Maine, Indian Country, and colonias (unincorporated rural communities along the U.S.-Mexico border) — with a few exceptions, predominantly counties where people of color are the majority.

Educational attainment and economic outcomes are also closely linked. Recent data shows rural Americans are increasingly well-educated, with the portion of rural Americans holding at least a high school diploma on par with urban.15 However, between 2000 and 2014, the gap between rural (19%) and urban Americans (33%) with a bachelor’s degree or higher grew from 11 to 14 percentage points.16

At the same time, recent research documents rising rates of mortality and lower life expectancy in many rural places, particularly those with higher poverty rates and lower educational attainment.17 Not coincidentally, rural places with poor health outcomes also have the most stressed health delivery networks; more rural hospitals have closed in poor communities than in other rural places.18 In rural areas where opportunity is hard to come by, the opioid epidemic has taken hold, sowing chaos and deepening hopelessness. These rural places have captured the headlines and demand action and solutions. Even so, they do not reflect the full breadth of rural America’s conditions or experience.

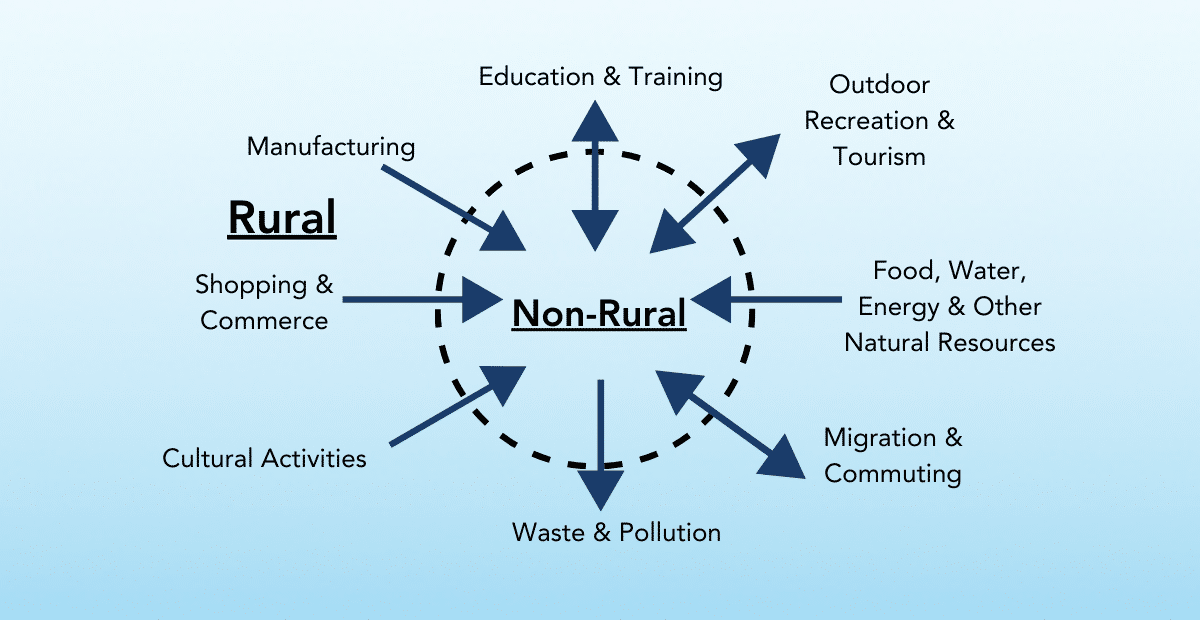

Rural and Urban are Connected in Interdependent Regions. Most rural areas and nearby cities are entwined in relationships that define regions. But this relationship is not always realized or acknowledged, much less acted upon, and it can be as complex and varied as the rural landscape. Rural-urban ties can have one or more underpinnings: common geographic conditions such as watersheds or mountains; supply chains that fuel industry sectors with services, goods and talent; transportation and affordability-driven employee commuting patterns; media markets; and the need (or mission) to secure a share of essential goods and services (such as food and energy) locally. In some areas, rural places and cities are reliable partners and provide important markets for each other. In others, intentional regional action is missing, and urban areas drain attention, energy or resources away from surrounding rural locales.

“Creative thinkers come from communities of different cultures and abilities — this diversity and engaging with underrepresented populations helps our placemaking be innovative.”

Cheryal Lee Hills, Region Five Development Commission

Rural is Resource-Rich, Resilient and Creative. Rural America has valuable assets, from water and natural resources to natural beauty, cultural capital, deep knowledge of place — and people with talent and resourcefulness. Some rural areas grapple with limited financial resources and acute infrastructure needs, such as antiquated water/wastewater systems or meager broadband. However, these constraints have also stimulated innovation and ingenuity in solving problems. The combination of few people, large geographies, challenges that extend across working landscapes (e.g., forest and watershed regions that span counties), and serious resource constraints can motivate collaboration across political boundaries. It can induce working together as partners, rather than as competitors, especially when there are too few resources to go it alone.

Rural Development and U.S. Policy:

A Very Brief Recent History

100+ Years Ago. In 1491, North America was a predominately rural place — and had been for centuries. Hundreds of diverse American Indian and Alaska Native indigenous nations lived on these lands, and land was central to their worldviews, spiritual lives and ability to provide for themselves. When Europeans crossed the ocean for exploration and colonization, the control of land changed. Land west of the Mississippi was under French rule until the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. The Spanish controlled land from Texas to California and part of Mexico until 1845 and 1848. The British took hold of the Oregon Territories of the Pacific Northwest until 1846. Native Americans consistently questioned and resisted colonial claims.

Initially, the economy of the growing nation-in-formation was largely agrarian. Much of its success was built on the labor of Africans captured and brought to America as slaves, on indentured servants from Europe who worked for a contracted number of years in exchange for their passage to America and their room and board, and on other low-wage labor. The colonies of the “new world” produced raw material for the more industrialized “old world” to process and sell across their domains. Eventually rejecting this mercantilist system, the northern states and colonies launched centers of industry and cities to go with them. At the same time, southern interests that benefitted from the slavery-dependent agricultural “raw goods” trade economy fought to defend the status quo.

The size of the United States and U.S. territories grew rapidly during the 19th century. The federal government began developing policies to populate new areas with newcomers. Canals, railroads and road systems were constructed to move people and goods thousands of miles across the country. Efforts to relocate American Indians became increasingly aggressive.

Starting in the 1860s, the Homestead Acts — a series of laws establishing ways for Americans to acquire land — opened up millions of acres and westward population expansion began in earnest. For this still largely agrarian nation, President Abraham Lincoln in 1862 created the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and with it the Land Grant University and Cooperative Extension System. While discriminatory, for years, the Department of Agriculture’s policies were seen as a means of stabilizing the rural economy and millions of rural families engaged in agriculture.

The end of slavery prompted radical change in the economic and social order of rural and urban communities alike. African Americans began moving north to largely urban centers in the Northeast and Midwest in search of opportunity. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with a larger, increasingly dispersed population, federal lawmakers paid close attention to the local and regional effects of federal policy. For example, the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 sought to create an equal playing field for businesses in all regions, including less populated ones, by ensuring that railroad rates did not favor one community over another by size.19 In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson plainly expressed the value of federal policy support for local economies: “…if America discourages the locality, the community, the self-contained town, she will kill the nation.”20

A majority of Americans still lived rural, connected to farming in some way, up to World War I. Even after that, at the height of the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt signed into law programs designed to support the agricultural economy and improve conservation practices. At the same time, technology was mechanizing agriculture and reducing the demand for farm labor, even as demand for workers boomed in manufacturing centers. This prompted more migration to cities — including millions of African Americans moving from the largely rural south to the urban north to make a better living.

50+ Years Ago. In the 1930s and 40s, the federal government made a concerted effort to address rural poverty. The New Deal’s Farm Security Administration — known for stunning photography of rural poverty in the Dust Bowl — provided education and relocation assistance to families living on exhausted, unproductive lands. Its successor, the Farmers Home Administration, provided loans and grants for housing, water systems and rural development. Concurrently, the federal government made hefty investments in rural public works infrastructure through new programs including the Civilian Conservation Corps, Tennessee Valley Authority and Rural Electrification Administration. Social Security and other social initiatives, such as the Rural Housing Act of 1949, contributed to improving the quality of life in rural America. These ground-breaking, national-scale efforts were designed to usher all U.S. regions into the modern era, as technological innovation continued at accelerating speed.

Around the same time, the federal government enacted new “termination” policies in the 1950s, ending its recognition of a large number of American Indian tribes. With these policies, the government withdrew vital social services guaranteed by treaties and launched a relocation program that provided American Indians incentives to move to large American cities. This resulted in the urbanization of approximately 750,000 Native people.21

In the 1960s, images of abject poverty in Appalachia and other rural places hit national television screens via documentaries and political campaigns. In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson created a National Advisory Commission on Rural Poverty.22 Among other things, the Commission recognized that the very technology changes driving increases in agricultural efficiency and production were exacerbating rural poverty. It also found much of America’s rural poverty to be structural in nature, the result of policies and laws that systematically — if unwittingly — put rural places at a disadvantage.23 The Commission’s 158 recommendations ranged from increasing access to education to improving health care.24 Many were implemented and measurably improved day-to-day life for millions of rural people. In 1975, Congress enacted the Indian Self-Determination Act, a vital piece of legislation that ended the destructive termination policy and provided tribes with a wide range of opportunities to contract directly with the federal government to provide health, education and other services.25

However, the rapid influx of corporate innovation and technology that jolted rural America before 1970 was a harbinger of quakes to come. The post-war growth of the 1950s and 1960s halted amidst double-digit inflation and two oil crises, prompting a political leadership change.

The 1980s ushered in a new policy era favoring tax cuts and deregulation and, with them, significant reductions in federal funds to states and localities.26 By the 1990s, the globalization of the economy and trade were in full force, hallmarked by the North American Free Trade Agreement and the World Trade Organization. These changes, coupled with a growing emphasis on productivity, efficiency and shareholder benefits, fundamentally changed the nature of rural economies. Big-box stores strained and drained independent businesses on Main Street. Corporate restructuring and consolidation transferred business ownership to outside holding companies and “accountability” to absentee shareholders far removed from the communities where their businesses were located — and where their employees lived and worked. Offshoring led to the closing of rural factories, call centers and firms up and down sector supply chains.

In the 21st Century. These changes forced small towns and rural places to reinvent their communities and economies. Despite many bright spots, hopeful data points and valid counter narratives, the breakneck pace of technology and economic restructuring of recent decades has been hard on rural America. Rural places took longer to recover from the Great Recession than most cities.27 Though thriving rural towns and regions dot the nation’s landscape, the overall rates of unemployment, child

poverty, educational attainment, food insecurity, obesity, health coverage and other quality of life indicators are worse in rural than in urban areas.28

Today, manufacturing and natural resources — such as timber, mining, natural gas and oil — remain key pillars of the rural economy. But in many places, other sectors — service, outdoor recreation, tourism, health care and the public sector, including education — are increasingly important and dominant. Agriculture remains a key driver in some places, although nationally less than 5% of the rural workforce is employed in agriculture.29 Each of these sectors is experiencing both positive and not so positive trends — depending in part on place, strategy and leadership. The devolution of government and the growth in unfunded mandates make it hard to develop and implement strategies to address these trends, no matter their direction. So do spotty broadband coverage in an increasingly information-connection economy, and the scant resources under local control in multi-community rural regions.

While policy in many cabinet departments and agencies affects rural places, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), at least on paper, holds responsibility for coordinating rural policy across the federal government. Today, the Rural Development Program section of USDA is home to modern-day incarnations of several (but not all) 20th century agencies, authorities and programs created to combat rural poverty and to improve the quality of life in rural America. Many (but not all) of the laws that govern USDA Rural Development’s programs are reauthorized and revised via the “Farm Bill” — the omnibus farm, food and rural legislative package that Congress considers approximately every five years. Most attention to the Farm Bill — and lobbying around it — fuses around its component titles that deal with large commodity crops, land use and nutrition (e.g., the SNAP/food stamp program). The Rural Development title of the Farm Bill, which contains critical programs that aid the non-agriculture side of rural community and economic development, gets much less attention in the Farm Bill reauthorization process. That is because the non-ag rural development components of the bill are dwarfed by the commodity and nutrition programs, and because their funding levels are not determined by the Farm Bill, but via the annual appropriations process. Today, many programs and policies important to rural America are found in agencies other than USDA. All the same, it is USDA that has the mandate to tend to national rural policy — and that has offices in small towns and rural regions throughout the country.

While rural places have both been subjected to economic change and have changed themselves in recent decades, proposals to build stronger rural places have largely stayed the same. Across the political spectrum, federal policy proposals recommend more strategic use of direct service programs (e.g., Medicaid) — via better coordination, implementation and/or service expansion — and investments in rural infrastructure, especially broadband. These proposals would markedly improve the economy and quality of life in rural America. But they are not enough to vault rural places into diversified, durable and inclusive economies that improve social and economic outcomes for all. These proposals do little to

address the structures, systems and policies that routinely — if inadvertently — disadvantage rural people and places. Rural America needs some large-scale, systemic policy change at the federal and state levels, including an examination of whether or not the programs of USDA Rural Development align with modern rural realities. Rural America also needs a fresh approach to economic and community development — and more people and places that understand and practice it.

A Fresh Approach to Community and Economic Development

Over the last century or so, economic development efforts have been dominated by one primary focus: attracting businesses to locate — or relocate — and then grow in a place. Though people in the development profession do many things in their jobs, business attraction’s prevalence, promises and ribbon-cutting visuals have mistakenly shaped the popular image of what “economic development” means. This, in turn, has induced multi-state competitions with business-attraction packages that nationally total $80 billion a year — incentives whose zero-sum net effect is to starve many communities of the resources they need to finance essential services for their people and places.30,31

Parts of rural America benefited greatly from business attraction at one point — though often to the detriment of other places. For example, in the latter 20th Century, textile companies moved to the South from the Northeast, and auto manufacturing and supply chains moved from Great Lakes cities to rural locales around the country. A few decades later, many of those same businesses moved offshore, leaving those rural places behind.

Other parts of rural America — especially those capitalizing on their natural resource base through drilling and mining, corporate agriculture, timber and paper — have experienced booms and busts. The busts have been occasioned by corporate consolidations, trade policies and pricing, as well as by global change trends such as the transition to using and producing cleaner forms of energy.

Heavy on attraction and extraction, these “traditional” economic development approaches have been a rural mainstay. Their singular focus on growth and jobs as the primary measures of success has now proven insufficient — and sometimes ineffective — at improving rural economic and social outcomes over the long run. Resource extraction and business attraction will always have a place in rural economies. But especially in rural regions, it is time for a fresh approach to community and economic development.

“We must do economic development differently. We must make bold moves to shift our economy away from inequitable extraction of resources and towards a collective, inclusive vision of the future.”

Heidi Khokhar, Rural Development Initiatives

The good news: Alternatives exist and Rural Development Hubs are practicing them. The emerging “wealth-creation” method — whereby communities build on what they have in order to do community and economic development differently — is based in part on the asset-building approach to community development championed by John McKnight and Jody Kretzmer, as well as Cornelia and Jan Flora’s “Community Capitals” framework.32,33 This approach focuses on generating and retaining a range of capitals within the community, reinvesting that wealth for future productivity, and improving the quality of life for community residents, rather than on viewing only growth and jobs as the primary measures of success.34 Investments in local people, local institutions, local resources, local partnerships and local systems are considered as essential and foundational in this development toolbox as are investments in infrastructure and firms. We call this asset-based, wealth-building and more encompassing approach “Doing Development Differently.”

Evidence of this new approach in action is mounting. Efforts to build regional and local food systems as well as “the 50-mile meal” (shortening the food-to-plate travel distance) are perhaps the most widespread and well known. Other clear examples can be found in North Carolina’s textile industry, Appalachia’s wood products sector, Delta biofuels production, housing-related community development in the Texas borderlands, modern wood heat and outdoor recreation in the Northeast’s Northern Forest region, manufacturing in rural Minnesota, helping rural low-income families get ahead in Maine and western Maryland, and among Great Plains entrepreneurs. Key to a few emerging community wealth-building strategies is using “anchors” such as hospitals and colleges or tribal enterprises to center and distribute new local economic activity.35,36 A resurgence of cooperative-ownership initiatives in several industries is increasing inclusive local ownership and benefits. Practitioners in the “localism” movement have developed an ecosystem framework to guide communities in “how to build a healthy, equitable local economy.”37 Also gaining traction, WealthWorks — which embraces many of these frameworks in one approach — focuses on developing “value chain systems” of regional activity in order to build and root local wealth, while always including those on the economic margins in the action and the benefits.38

This emphasis on local people and institutions and regional systems flows from the understanding that people are at the heart of a community and its future. It is local people and institutions that must produce strategic and viable decisions, actions and investments to improve outcomes. But how does this get organized in rural places? Large municipalities may have planning departments, economists and expert staff devoted to making their economy work, but most small town, rural and regional governments do not. In rural places, the work of identifying a region’s assets and determining the investments that will help build a vibrant, inclusive and durable local economy is best done by community leaders and local organizations — such as Rural Development Hubs.

Rural Development Hubs:

Not Just Any — Or Any One Kind — of Intermediary

Pursuing a development approach that generates inclusive wealth creation and investments in people, firms, sectors and systems requires an organization capable of doing what it takes: systems thinking and weaving, enterprise development, innovation and more. In the rural places where development is being done differently, a certain set of intermediaries — Rural Development Hubs — are typically leading the effort.

But first, what is an “intermediary”? Intermediaries are place-based organizations that work to improve prosperity and well-being by harnessing local and outside resources to design and deliver services and products to people, firms and organizations in their region. As MDC authors described back in 2001, intermediaries “sit in between the realms of local action and national policy.”39 Intermediaries provide an array of services to local organizations, firms, entrepreneurs, individuals and families, while simultaneously providing eyes, ears and boots on the ground that can inform state and federal agencies, foundations and others — and knit them into the action.

Thousands of rural and regional intermediaries operate in the United States. But not all are created equal. Not all intermediaries work on community and economic development, and those that do may favor the “old school” traditional methods. Of those that do community and economic development, some focus on the “people” side — for example, community action agencies that provide services and support to low-income individuals and families, or community colleges that prepare people for careers. Others, such as community development financial institutions, provide finance and assistance to small businesses. Still others, such as community foundations, have flexible missions focused broadly on community betterment.

Within any category of intermediary, some choose narrow missions that are largely transactional; they focus on efficient delivery of resources and services — a good thing. We need such intermediaries to address the immediate needs in a region, but their transactions rarely change the rules or the system. Others seek to transform — to go beyond treating symptoms by working to cure and prevent the “disease” that caused the symptoms. It’s the difference between efficiently providing food to hungry families through food kitchens (transacting) and helping these same families change their circumstances and thrive so they no longer need food assistance (transforming).

The transformers fit our definition of a Rural Development Hub. The main players in rural America that are doing development differently, Hubs think of their job as identifying and connecting community assets to market demand to build lasting livelihoods, always including marginalized people, places and firms in both the action and the benefits. They focus on all the critical ingredients that either expand or impede prosperity in a region — the people, the businesses, the local institutions and partnerships, and the range of natural, built, cultural, intellectual, social, political and financial resources. They work to strengthen these critical components and weave them into a system that advances enduring prosperity for all.

Again, not every intermediary working in rural America has the qualities of a Hub. And there is no one “kind” or “category” of rural intermediary that is reliably always a Rural Development Hub. For example, in our research, we engaged 43 Rural Development Hubs drawn from a wide range of intermediary categories, including:

- Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI). Private financial institutions dedicated to delivering responsible, affordable lending to help low-income, low-wealth and other disadvantaged people and communities join the economic mainstream.

- Community Development Credit Union (CDCU). Credit unions that serve low-and moderate-income people and communities, especially populations with limited access to safe financial services.

- Community Development Corporation (CDC). Nonprofit, community-based organizations focused on renewing their community — typically low-income, underserved areas that have experienced significant disinvestment — by rehabilitating buildings, establishing new businesses, and creating jobs for residents.

- Community Action Agency (CAA). Quasi-governmental organizations with a mandate to provide services to needy populations and connect them to greater opportunities in specific geographic regions. By law, CAA executive boards include low-income community members.

- Community Foundation. Public charities dedicated to improving lives and conditions within a defined local geographic area. The most flexible form of nonprofit, they can bring together the financial resources of individuals, families, businesses, government and other foundations, and use a wide range of tools to effect change — grantmaking, building locally controlled funds and endowment, fiscal sponsorship, convening, investing, lending and running programs. Many have geographic component funds or geographic affiliates that give them a wide reach in rural communities.

- Health Legacy Foundation. Sometimes called health conversion foundations, created when a nonprofit health organization (e.g., a hospital) is sold to a for-profit entity or when one transitions to for-profit status. Federal law requires that the proceeds of the sale be placed into a nonprofit foundation, which typically serves the same geographic region that the health organization served.

- Family Foundation. Derives its funds from members of a single family, sometimes over multiple generations. Its decision-making board includes one or more members of that family. Some family foundations dedicate all or part of their philanthropy to specific geographic areas.

- Statewide and Multi-State Foundations. Mission-driven private foundations with a geographic focus and/or an economic and social equity focus.

- College and Community College. Degree and certificate- granting institutions that provide academic and technical education and workforce raining, ideally with some focus on jobs in industries based in its region.

- Statewide Rural Organization. An independent nonprofit that works statewide to analyze rural conditions, run programs, and advocate for policy change.

- Social Enterprise/Cooperatives. A nonprofit organization or collaborative that operates businesses as part of its mission — or vice versa —both to generate revenues and improve economic, social, equity and environmental outcomes for people and places.

- “Unicorn” Regional Organization. A free-standing nonprofit that does not fall into any other category. It works to improve an aspect of rural/regional economic and social well-being within a defined geographic area, which may include areas in more than one state.

It’s notable that government agencies do not appear on this list, nor do any organizations that are called economic development agencies. Public and development agencies do play important roles in rural development — and some are quite creative at it. But most of the visible innovation in doing development differently in rural America is being advanced by Rural Development Hubs that identify in one of the categories listed above.

The Hubs we interviewed play a catalytic and transformative role in their regions and communities. They are not focused on meeting immediate needs alone. They also aim for and deploy systemic and long-term interventions and investments that have the potential to strike at the root causes of poor rural social and economic outcomes and to strengthen the essential components that form a better foundation for lasting prosperity.

What Sets Rural Development Hubs Apart?

In recent decades, plenty of documented stories have surfaced about rural intermediaries stretching their missions and organizational boundaries to improve regional outcomes. We interviewed dozens of these “stretching” Rural Development Hubs to delve into what sets them apart from other intermediaries. Here is what our interviews and experience surfaced.

1. Hubs think and work “Region.”

Hubs use a regional mindset and pursue regional action, regardless of whether their work starts in one community or crosses state lines. They cite several reasons:

- A place cannot do well — or better — without connections. The existence, linkage and relative strength of connections within a region make a difference on outcomes.

- Most development work is hard to do alone, and because of low density and large distance, the partners necessary to do rural development typically are spread across a region, rather than all located in one town.

- Industry sectors that drive economies tend to be regional, so the region becomes a natural action zone.

- Scale matters. It is easier to negotiate with other regions and outside stakeholders as the critical mass of a “region” rather than as one organization or community. And working across a region better enables a Hub to assemble sufficient resources and work needed to maintain its efforts and organization.

Not only do Hubs think “region,” they induce others in their area to think “region” as well. This role is important because very few policy incentives encourage regional action. Rural actors often come to the table thinking about their own town or issue — not about regional connections or mutual reliance. Things as simple as high school sports rivalries among neighboring towns reinforce go-it-alone thinking, as do differing jurisdictions, elected leaders and governance. City residents, by contrast, may live in competing neighborhoods, but often think about the city as a whole — and are indeed legally part of that city, which makes it more natural to work together.

2. Hubs Assemble the region for discovery and dialogue.

Rural regions are home not just to multiple organizations, but to numerous political and municipal jurisdictions. The region of one Hub we studied, for example, includes a school district, a hospital, three counties, multiple towns and villages, and 15 additional special districts with varying footprints, all to serve roughly 33,000 full-time residents. This complexity, coupled with cumbersome and widespread geography, makes getting together, let alone doing anything together, time-consuming and difficult. Again, this is different in cities, where it’s logistically — in time, transportation options and distance — easier for people from several neighborhoods to gather.

And though perhaps a blinding flash of the obvious, here is another key point: There is no “government” of a rural region. No one “holds the whole.” No one has the official or assigned responsibility for a rural region’s welfare and action. In some places, a regional forum might exist — for example, a regional council of governments — but often it has limited scope and cannot take the risks essential to innovation.

A Hub steps into this void. Someone has to call the meeting. When a discussion must be had or an issue addressed, Hubs tend to be conveners, bringing together the region’s stakeholders across profession, politics, place, sector, role and class. They provide a safe place for dispersed and diverse actors to hash out the tough stuff of how to improve the livelihoods of people, place and economies. As intermediaries evolve into Hubs, our research shows, they typically become entities that look at the region as a whole, and provide the space (physical and psychological), the organizational flexibility, and the whole-region perspective to host and lead essential conversations.

3. Hubs are of their region, know their region, and are widely and deeply trusted in their region.

Hubs live and work in the places they act in. This gives them an authentic voice. They also “show up” in the region, not just for work, but to build the understanding and relationships critical to making good decisions and working together. They travel far and wide to listen, be present, do work and become known. This way, when “things come up” and “stuff happens,” they bring ground-truth to the action and solutions table.

Hubs know that building trust — up, down and sideways — is essential to their work. Hubs find ways to consult, stay in touch, and build relationships with as many types of community actors as they can manage. Hubs understand this means meeting their customers where they are, and that their customers range from colleague nonprofits to business owners, workers, striving families trying to get ahead, new immigrant populations, and students considering their futures. Each is a source of information critical to what to do and how to do it. Hub leaders told us, time and again, that when they have buy-in from their region’s business community, political leadership, civic associations and residents, they have the power to move and change fundamental social systems.

4. HUBS TAKE THE LONG VIEW.

Hubs think long-term, with an unwavering commitment to their communities. Achieving lasting outcomes through community and economic development work requires a multi-decade arc. This underscores the often uncomfortable — yet essential — Hub role of assembling and investing resources for a long-term payoff in places where residents have many immediate needs. As Clark Casteel of the Danville Regional Foundation in Virginia, noted, Hubs are in “…the transformation business, not the happiness business.”

This long-term commitment to a place, knowing that an intermediary isn’t going anywhere, is a vital ingredient in building the trust that enables collaboration. Patrick Woodie of the NC Rural Center offered: “As we enter our 33rd year, we have built deep trust and strong relationships with our rural communities, and we know they see the Rural Center as ‘one of us.’”

Taking the long view also liberates Hubs from jumping on the latest “action sensation” bandwagon. Instead, they take their cues from the community — and from careful analysis of what is going on. The end result, according to Heidi Khokhar of Rural Development Initiatives in Oregon: “Ultimately, if we do our job well, rural places have a living economy. They have strong community, are resilient, self-determining…It’s not something that happens in two-to four years.”

5. Hubs bridge issues and silos.

Hubs are the antidote to “siloed” action. “Siloed” has almost become a trite expression except it is still true — many rural (and urban) organizations and efforts focus on one isolated issue or aspect of a challenge and stop there. Some realize that their work is only alleviating symptoms, not tackling root causes. But the limits of their mission stops them, or they feel unequipped or too stretched to do more.

However, economic and social challenges are rarely caused by one factor. They can’t be fully addressed without addressing a “system” of linked factors. Feeding hungry children, for example, is a good siloed thing to do. But unless the children’s family situation changes, they will be hungry tomorrow. Likewise, a region can offer excellent training programs for would-be workers. But unless the programs are connected to the region’s businesses and the skills those businesses need, the training may not lead to landing a local job or produce value for the region.

Within a geographic region, effective intermediaries like Hubs can, as regional sociologist Ralph Richter puts it, “…not only bridge social and spatial but also cultural gaps. They represent the capability to link different worlds, whereas most of the other players are either involved in one or another of these environments.”40

6. Hubs analyze at the systems level, and intentionally address gaps in the system.

Mission, scope or funding streams often limit the ability (real or perceived) of local organizations to respond to community priorities or needs. Our interviews indicate that Hub leaders, no matter the type of organization, look beyond these limitations to take a wide view of their geographic, economic, social and cultural responsibilities.

Hubs tend to intentionally — or by nature — think “system.” They try to figure out whether the system is making things worse or is generating opportunities to make things better. They map the components or factors that perpetuate current outcomes or that could produce desired ones. They look for missing links in the system that demand action, or for underutilized resources that present opportunity. Rather than limiting themselves to their organization’s primary and required functions, they think creatively about assets and gaps — how to build the most from community assets, and how to plug gaps within regional systems through new enterprise or partnerships that produce local value. For Hubs, good is not good enough; it is all about getting to better.

7. Hubs collaborate as an essential way of being and doing.

To do community and economic development differently, Hubs convene networks and create collaborating systems that otherwise wouldn’t exist, across multiple political and jurisdictional boundaries as well as extensive rural geographies. Some even see it as part of their performance framework, meaning that they hold themselves accountable for collaborating and view collaboration as a sign of a healthy organization and growing community vitality. Building collaboration is not just a technique; it is in the DNA of Hub organizations.

Others have signaled the importance of collaboration in taking on community and economic development. In a 2014 address to the Boston Federal Reserve, Rip Rapson, CEO of the Kresge Foundation, underscored this: “…[C]ommunity and economic development presents a constellation of challenges so densely packed, intertwined and complex that the solutions must be systematic, not atomistic; dynamic, not rigid; long-term, not episodic; participatory, not hierarchical. It will be the increasingly rare circumstance in which these challenges can be resolved through neat and tidy technical interventions. Instead, communities will have to bring to bear multifaceted adaptive solutions requiring changes in beliefs, priorities and behaviors of multiple parties.”41

Collaboration is a Hub’s bread and butter. Hubs foster regional collaboration that cuts across economic sectors, and that can work to unite urban and rural spaces. Though a few Hub leaders we interviewed view other regional organizations as competitors, the overwhelming majority identify collaboration and partnerships as essential to their work. Their partners range from organizations within the region with varying expertise to organizations trying to do something similar but in a different part of the country. Ines Polonius, CEO of the multi-state Communities Unlimited, bottom-lined the rationale for collaboration: “In my mind, the work done in rural places is dramatically different when you are able to build a collaborative of stakeholders, rather than one-off partnerships. We need to lift up the difference. Collaboratives are time- and money-intensive. But once you have collaborative systems in place, change begins to accelerate.”

8. Hubs create structures, products and tools that foster collaborative doing.

Regardless of whether their main mission is to provide direct services to families or to build business ecosystems, a central function of Hubs is to create structures — inventive products, services, programs or tools — that bring others more easily into right-sized collaborative action. They work horizontally and vertically across the political and resource spectrum to achieve results. A few examples:

- During the recent federal government shutdown, within one week, a CDFI Hub that had never done consumer lending developed a new instant loan product to help area residents employed by the federal government or its local contractors. The Hub recruited a local bank, a local employer and a foundation to collaborate. Absent that product and the Hub’s relationships, no collaboration.42

- A rural community action association Hub launched a certified car dealership and a family car ownership program after realizing that transportation was an insurmountable obstacle preventing striving but struggling rural families from getting ahead. The Hub engaged several public, foundation and private partners, and the effort improved family outcomes on multiple measures of well-being, more effectively than many of the agency’s other poverty-fighting programs. Absent the car ownership product and dealership structure and the Hub’s relationships, no collaboration.43, 44 Several Hubs that are rural community foundations assembled regional workforce development collaboratives in their service areas, pulling local banks, employers, colleges and charities into the action, along with state technical assistance programs, university research, international experts, federal dollars — and more. Absent a Hub providing a coordinating backbone and its relationships, no collaboration.45, 46, 47

- An enterprising rural nonprofit Hub linked multiple partners’ efforts into a strategy to help single low-income mothers pursue college degrees and secure jobs while pursuing other family-strengthening goals for themselves and their children. The initiative was formalized through an unprecedented joint memorandum of understanding (MOU) among seven organizations that clearly spells out each organization’s responsibilities, with a local economic development agency serving as the effort’s home base. Absent the MOU tool and the Hub’s relationships that landed the effort a permanent home at the economic development agency, likely only a tenuous collaboration.48

The will and ingenuity to develop these mechanisms and tools, over time, builds relationships among collaborating organizations and understanding of each organization’s expertise. This helps Hubs and their partners tackle more complex challenges the next time they arise.

9. Hubs translate, span and integrate action between local and national actors.

Groups working at the community level grasp what has worked and not worked locally. But they tend to lack the resources to connect to trends, innovations and funding sources elsewhere, especially at the national level.49 Likewise, many national and state leaders who marshal significant resources have a notional understanding of what rural communities need but lack the will or means to tailor action to specific rural places.

Hubs bridge the gulf between macro-scale rural economic development policies and micro-level community action, and do so in ways that transcend political boundaries.50, 51 This work of connecting and translating between national, regional and community-level efforts and actors is important to rural development. The flow of ideas to and from rural places can be slow — made worse by the ongoing collapse of local newspapers and media outlets, not to mention spotty, substandard rural broadband coverage. In addition, national and state policy tends to be developed with urban places in mind, with limited understanding of the impact on the variety of rural places and economic bases.

Hubs know this, which leads to two kinds of Hub work. First, Hubs track federal and state policy and investors — including government, foundations, corporations and other investing funds — or strive to do so. They figure out what’s available that applies to their region and tap it when possible. Second, when they can, Hubs inform policymakers and investors about how policy or investment design, requirements or restrictions help or hinder investment in rural places. And they advocate for changes that will facilitate healthier rural development.

10. Hubs flex, innovate and become what they need to become to get the job done.

Overwhelmingly, Hub leaders described their organizations and approach to working in the community as entrepreneurial. Hubs fill gaps and offer programming, services and products that are beyond the mission, scope, reach or interest of their region’s other institutions. For example:

- Thirty-five years ago, few (if any) U.S. community foundations conducted business lending. This changed when rural community foundations in Minnesota spotted the need to fill business lending gaps in their regions that no one else would. Local business sectors could not modernize and improve jobs and wages without these gap loans. Community foundations in the state banded together to secure an Internal Revenue Service permission letter enabling them to lend to businesses as a charitable activity in areas of economic distress. Today, many community foundations lend to businesses —especially in rural America.

- In Texas, the Brownsville Community Development Corporation launched in 1974 with the goal of eliminating the community’s 1,500 outhouses. It moved from doing “just outhouses” to housing rehabs to new workforce housing construction, evolving into an equity-focused comprehensive housing organization. When more and more clients with low credit ratings needed housing, the Brownsville CDC began building multi-unit housing and rental properties — and also developed methods to provide financial education and credit-building services. It was one of the first CDCs in the country to create a revolving loan mortgage product using Community Development Block Grant funds, a technique that has since been adopted nationwide.

- The Land Buy-Back Program was the U.S. Department of the Interior’s “…collaborative effort with Indian Country to realize the historic opportunity afforded by the Cobell Settlement — a $1.9 billion Trust Land Consolidation Fund — to compensate individuals who voluntarily chose to sell fractional land interests for fair market value.”52 The Buy-Back Program prompted many American Indian tribal members to sell their interest in parcels of land. For some, an unintended consequence was losing the collateral essential to accessing credit. In the wake of the initial stream of buy-back activity, NACDC Financial Services, in Browning, Montana on the Blackfeet Reservation, created a short-term loan program so that Tribal members who had sold their land interests could access a line of credit, absent collateral.

Every Rural Development Hub has a story like this. One Hub leader, Peter Kilde of West CAP, Inc. in Wisconsin — the agency that developed the low-income car ownership program mentioned earlier — pointed out that this flexing and innovation can happen only if a layer of readiness is in place to attract and absorb necessary resources in the right way: “You can’t just throw money at a region and have it do what you want it to do. There are things you have to do first to get people ready and networks underway.”In short, Hubs do in their regions what others with limited scope, funding constraints, lack of will or meager entrepreneurial muscle will not. What Hubs decide to do, or what they decide to morph into, emerges from consulting with the community and seeking a fuller analysis of the system. It results from constantly asking why and a persistent, eager search for how.

11. Hubs take and tolerate risk.

Taking risks is fundamental to innovation. Hub leaders cite risk tolerance as critical in their move from a transactional to a transformative organization. And it has to start at the top. Some Hub CEOs reported investing significant time and energy to foster a board culture comfortable with both risk and the possibility of failure. Discussing a pivotal moment when the Neil and Louise Tillotson Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation adopted new risk and decision-making processes, director Kirsten Scobie cited the Tillotson Fund advisors’ rationale: “If we really want to make change and be part of catalyzing this region that has been in decline, we have got to be bold.”

Hubs’ bias towards bold action is a frequent refrain. Chrystel Cornelius of First Nations Oweesta Corporation in Longmont, Colorado, put it plainly: “We need to keep pushing boundaries, doing uncomfortable things, being in places that we normally are not. We need to have the tenacity and thicker skin to take rejection well and keep on going.”

12. Hubs hold themselves accountable to the community — the whole community.

The community is the heart of a Hub’s work. When asked, “To whom are you accountable?” the overwhelming majority of Hub leaders responded that their organizations are primarily responsible to their community. Of course, they also cite fiduciary duties and responsibilities to investors, funders and the government. But their reputation in the community and the community’s trust is paramount to their ability to be effective. The Northern Forest Center’s Rob Riley reinforced this point: “There is accountability to the board, but we feel really accountable to stakeholders in the region. That, to some degree, is how we measure impact. It’s about being respected and sought after because people know we can get the work done; it is the promise of what we can bring to a partnership.”

Some noted that their work responds to a disaffected community’s search for hope, opportunity and a new way of living. For Rural Development Hubs, the highest aspiration is creating vibrant communities where everyone can participate — in the economy, democracy and decision-making. Hubs know they have a place in the arc of positive change as they work to transform a place of need into a place of hope.

Voices from the Field

“In a rural place, there aren’t enough resources to go it alone…The model for collaboration that is essential to rural America is the church potluck supper. Everyone brings what they can to the table, and you end up with more than you need to get your job done.”

John Molinaro, Appalachian Partnership, Inc.

“Thank God for our extreme isolation… because it has created a very entrepreneurial spirit in agencies like ours.”

Nick Mitchell-Bennett, Community Development Corporation of Brownsville

“What sets the work of The Industrial Commons apart is the comprehensive nature of what we do. Some organizations are focused just on workers, just on economic development, just education, just technological advances in workforce. Here, all are under this house, in an interconnected way. We hope it doesn’t make us a jack of all trades, master of none, but rather that solving one problem naturally drives solving another problem.”

Molly Hemstreet, The Industrial Commons and Opportunity Threads

“When you look at how a region functions, these imaginary lines of cities and counties don’t mean a lot in terms of economic development and how people are able to better themselves.”

Mike Clayborne, CREATE Foundation

“We are accountable to the people whom we serve and to our investors. One thing we have going for us is we have the trust of the community. If we should ever lose that trust, we are going to be out of the business. For us, that is very key.”

Jennie Stephens, Center for Heirs’ Property Preservation

“Because we are in the community… [we] are able to understand the communities we are working with. It enables us to be so successful. We grew up with these people. We understand their needs, their cultures.”

Angie Main, NACDC Financial Services, Inc.

Why Aren’t There Stronger — and More — Rural Development Hubs?

There are likely thousands of rural and regional intermediaries. Why haven’t more become Rural Development Hubs? Why aren’t some Hubs more robust? Here are some hindrances and challenges that face Hubs — and would-be Hubs — in their pursuit to transform their communities.

1. There is no business model or blueprint for Hubs. Sustaining a Hub is hard creative work that requires constant attention.

Hubs work to transform regional community and economic development outcomes. To do this, a Hub — regardless of whether it’s a CDFI, a community foundation, a community college or another type of intermediary — must constantly identify, raise, blend and braid streams of funds, large and small, from multiple sources. Each source requires its own use restrictions, outcome expectations, relationship development and maintenance, and evaluation and reporting duties. This happens because most funding, public or philanthropic, that Hub organizations can tap is structured to advance specific and limited activities or projects — usually related to a particular issue: education, housing, financial literacy, and so forth. In some cases, the activities a grant funds align with the Hub’s plans. In many cases, Hubs must shoehorn what they are doing to match a grant program’s design and requirements. In both cases, a Hub must still braid the funded activity with other funded efforts and manage all these distinct components in order to implement a silo-crossing initiative or system-changing effort.

What is not specifically or easily supported here is the Hub’s core staff and capacity to set and advance its overall strategy, develop and manage its internal operations, conduct regular analysis, act nimbly and flexibly to address unanticipated developments — and to raise and braid funds. Hubs generally shave off small pieces of whatever project funding sources they can to support these core activities and to build contingency funds. But this, of course, creates yet another time-consuming puzzle project for Hubs. In short, although Hubs pursue transformational work, most funding available to them remains siloed and transactional. The sources don’t match some critical uses.

Three factors add to this challenge of sustaining both the core capacity and the mission activities of a Rural Development Hub:

- Working in rural regions costs more — in time and money, wear and tear. The common assumption that doing anything in rural places costs less than in metro areas does not hold. Doing development work in rural regions with small populations spread across a wide geography adds challenges and costs. A needed one-hour faceto-face meeting even within the region itself might take hours or a whole day. Beyond that, just getting to a metro area or state capital for a critical funder or policymaker conversation, or for a conference, can take an entire day or two, plus there’s the cost of gas, wear and tear on a vehicle, and the strain and fatigue of frequent long drives. But Hubs must keep showing up — in order to build the relationships and trust essential to their work. Distance and low population density also increase the per-capita costs of service delivery. Many public programs are funded on a per-capita basis without regard to rural cost differentials. As a result, Hubs often must find ways to subsidize service delivery when per capita formulas fall short of actual costs.

- It’s hard to fund capacity-building and participation. It is commonly asserted that rural places and entrepreneurs lack access to business lending capital. This is true in some places. But a more common concern voiced by Hubs is the lack of a pipeline of local businesses sufficiently ready to use available capital. Many rural places have few or no business assistance organizations and are located far from any business assistance. Hubs that conduct lending take this seriously and develop technical assistance, coaching and other services to foster entrepreneurship and prepare businesses for financing — but this fundamental “readiness” work is harder to fund. Likewise, Hubs that help low-income families get ahead may be able to find funding for essential components such as financial education or skills training classes, but not to cover “soft costs” like the gas and child care that families need to participate — which due to distance, are critical in rural places.

- Trust-building and collaboration is hard to fund. Hubs, by necessity, use a range of partnerships and coordinated work to improve rural outcomes. Where the bench of organizations that can help is lean, collaboration is especially critical for making progress. But rarely does collaboration generate self-supporting revenue — and it always takes extra time and effort, usually more than anticipated. Although many investors and funders require and applaud collaboration — and understand its necessity — few fund what it takes to collaborate well, especially beyond the start-up phase. Hubs generally must patch together resources needed to sustain collaboration.

Each Hub must address its sustainability essentially as a separate project on top of the work they are doing to change regional outcomes. This massive effort typically requires an enormous amount of time from a Hub’s executive director and/or top deputy, if there is one. In short, a Hub’s most creative and entrepreneurial doers often spend more time securing and managing funds than figuring out how to best deploy funds in their community.

Even Hubs that appear to have a stable revenue base face challenges. CDFIs, which collect revenue from lending activities, still must find funding to build the know-how of striving businesses or to develop innovative products. Community foundations collect fees on the funds they hold — a model that was designed to sustain them when they were first founded over 100 years ago. But rural community foundations that go beyond grantmaking to spark collaborative action on critical issues must identify additional funding and partners to support this work, like any other rural Hub. Some Hubs thread this needle by working in both rural and urban areas or in both low- and high-income areas to balance their risks and revenue streams. Others create products that fill a need while also providing some revenue in return. For example, some CDFIs offer financial products to higher income markets, and others create technology and training products that are in demand — and saleable — to others around the country.

Hubs’ entrepreneurial activity is impressive — and laudable. But it’s hard work. The simple truth is: The challenge of establishing and maintaining Hubs as sustainable businesses keeps existing Hubs scrambling and keeps would-be Hubs from forming.

2. Hubs need entrepreneurial, cross-discipline, systems-savvy, innovative leaders committed to a rural region over the long term. Where’s the recruitment, training and sustaining program for this?

Hubs take on aspects of economic and community development that cross disciplines. A Hub leader who is trained in social work and runs a community action agency may need to learn about water infrastructure, business and construction finance in order to build affordable housing. Another Hub leader trained in business finance and running a CDFI may need to learn about building people’s credit scores and entrepreneurship training pedagogy. Leaders trained in English literature or non-profit management and running a Hub community foundation find they must learn how to “map a value chain” for their manufacturing, tourism or child care sectors. For Hub leaders, in the words of the old Department of Education postage stamp: “Learning Never Ends.”

This challenge extends to hiring talented young staff who might move into Hub leadership positions as part of a succession plan. Young people likely don’t even know that Hub jobs — which can be relatively exciting as jobs go — exist. Typically, young people have never imagined running a regional multi-disciplinary intermediary as a career track — and their school counselors haven’t either. Even if they do, they likely won’t find a college major that prepares them. Urban and regional planning curricula rarely focus much on rural, on the people side of economic development, or on non-profit management — and other relevant college majors are similarly narrow in scope. Of the young adults who do move or return to rural areas in their 30s with young families — and they increasingly do in some rural places — many have already established professions. Meanwhile, rural young people who don’t go to college or don’t leave the area also don’t know that good Hub jobs exist. Although they might be recruited for lower-level Hub jobs, they face the same cross-discipline and crossfunction learning challenges as their degreed peers do in order to move up the “Hub career ladder.”

Even existing Hub leaders who seek useful training can’t easily find it in one place. They must seek out multiple association and issue-focused learning groups and opportunities on the many topics their job entails. When they do attend a conference, workshop or webinar to learn about a relevant development strategy or tactic, they rarely hear a presenter based in a rural place or one who has an intentional sensitivity to rural differences and approaches. This challenge is compounded by the typically higher cost (in time and money) of traveling from rural places; a generally lower budget for professional development; and unreliable broadband coverage to access all-things- Web, including webinars and online meetings.The challenge of finding people to run rural Hubs is not due to a lack of leadership will or potential in rural places. It has more to do with specific knowledge about the job and how to do it. Rural Hubs’ hurdles to recruiting talent are akin to those that other rural professions face — with a twist. If it is hard to find a doctor to move to rural America — and it is — imagine finding someone to lead a multi-issue, multifaceted, cross-place and cross-sector regional development organization for which there is no training program. Despite this, we interviewed several field-leading Hub CEOs who moved to rural for their Hub job. They have sought and gained the additional learning they need, in typical entrepreneurial fashion. But it has not been easy. And it is not the norm.

3. Rural communities and leaders that might build Hubs are isolated from “what is possible.”

What you don’t know can hurt you. Organizations that could play a transformative role by becoming a Hub often do not because they don’t know the art of the possible. Why? Rural organizations often work in relative isolation due to geographic distance, or they lack a connection to strong networks of like-minded organizations because those networks are not easily accessible or simply don’t exist.

This “not knowing what is possible” is born out in the experience of many Hubs. For example, Hub community foundation leaders cite gatherings where peers explain something unusual that they do related to economic development — such as business lending, running an Earned Income Tax Credit program, buying a building, community organizing, or managing a workforce development collaborative. Some colleague rural foundation leaders respond with raised eyebrows and say, “I didn’t know you could do that as a community foundation.” Leaders of other types of Hub organizations tell similar stories.

Even if an organization’s staff recognizes the potential to play a Hub role, getting the board on board to move in this direction is a lot of work. Explaining this potential to board members is especially essential and useful. When board leaders see what organizations that look like them have accomplished as Hubs, a fire is lit — stoked by hope for their community’s future and by the competitive impulse inherent in some rural places. They begin to think: If they can do it there, we have what it takes to do it here.

4. Some rural communities resist change.

Rural America is sometimes characterized by rugged individualism, competitive spirit, skepticism — and a reluctance to change. Some rural places that do resist change can be tough nurturing ground for Hubs. Resistance can stem from four primary — and not mutually exclusive — conditions:

- The power dynamic is threatened. Hubs can develop position and influence by doing effective work and producing results. But Hubs sometimes threaten the powers that be — the “old guard” or the rising “up-and comers” — when they do things differently or take on some functions of a less effective local organization. Hubs build relationships and collaborations to overcome this, but they don’t always succeed.

- A negative perception persists of being “done to” by outsiders rather than “doing with others.” Rural communities can be understandably skeptical of non-local or national initiatives, especially if they have been burned in the past by failed promises resulting from short-term investments or by the damage left behind by extractive industries. Even within a region, a Hub may be perceived as an outsider; if it is headquartered in the region’s largest community, smaller towns in the area may deem it suspect. When a national organization sponsors that Hub’s initiative to benefit these skeptic communities, their concern can rise even further.

- Political divides eclipse action. Varying perceptions about who is doing the acting, why, and with what agenda can also foster resistance. Although rural leaders are typically unfailingly civil to each other, they also typically know each other’s small and large “p” politics. In rural places where politics has caused great rifts in the past, it can be hard to move any agenda that differs from the status quo.

- There is no will to change. Some places are comfortably intransigent. Their attitude is: What is new will never be better than the old — and what we have is just fine. Hubs — or anyone — can struggle to find partners or participation in these places.

These resistance factors can hamper the development of new Hubs and slow the success of existing Hubs. Getting over these hurdles can take generations of work. But it can be done.

5. Current and historic racism, discrimination, poverty and power inequities impede Hub development.

There is a direct correlation between communities with persistent poverty and communities with concentrations of people of color — in rural as well as urban America. In rural America, persistent poverty counties cluster in the Delta, in southern border states, in the Southeast, on American Indian reservations (the self-governing American Indian communities collectively defined in federal law as Indian Country) and in Appalachia. African American, Latinx and American Indian people comprise the majority population in most of these places, except Appalachia. In many, systemic racism persists in the economy and institutions, from the education system to hiring by local businesses to the health care system to social circles. This continues to generate inequities in power, wealth and income, as well as poor social, economic and health outcomes.

Also, the simple truth is: Size Matters. The needs and priorities of a rural town of 800 are often subsumed by the will of a neighboring rural town of 20,000. The interests of that rural town of 20,000 rarely register on the priority radar of a nearby city with a million, or of the state that houses them all. This power disparity repeats itself in domains from business investment to health care to education to funding formulas to elective office, and on and on.

Taken together, poverty, racism, structural discrimination and community size create an unmistakable power differential between rural and urban America. Rural places and populations have tremendous individual, social and cultural capital and potential. But they are victim to chronic disinvestment, weak infrastructure, limited financial capital, and a scarcity of durable, productive connections to power, critical resources and funding streams. This manifests in rural America as poor broadband, a lack of good jobs, low wages, scarce or distant services, prices for basic goods, poor quality housing, unaffordable health insurance, low access to quality health care, and diminishing opportunity.