Download as a one-pager here.

Knowing what is true about rural places and people is a challenge. Too often, people lump all of rural America into one “flyover-country” stereotype. But saying that all of rural America is the same is like saying Detroit and San Francisco are the same or Birmingham and Boston. This blog shares a few truths worth knowing about rural America.

Key Facts:

- 19.3% of the US Population lives in rural America, about 60 million people.

- The number of people living in rural America increased 11% from 1970-2010.

- Agriculture employs less than 5% of the rural workforce.

- People of color comprised 83% of rural population growth between 2000 and 2010.

- In 2017, the rural poverty rate stood at 16.4% compared to urban at 12.9%.

- For children, the rural poverty rate was 22.8%, more than five points higher than urban at 17.7%.

Rural America Varies Widely – by Economy and Geography

Rural is typically defined — even in national data — as “non-metropolitan” or “non-urban.”1 This doesn’t tell us much. Perhaps due to this lack of precision and our nation’s agrarian roots, people still commonly equate rural with agriculture, fields of corn, cows, and hardscrabble farmers. This is not only inaccurate; it is wide of the mark. From vibrant college towns to communities gone bust from the flight of paper mills or coal mines, from hopping cultural tourism locales to centers of furniture, machinery, and textile manufacturing, rural America is anything but simply farmland, and it is anything but uniform. Rural New England, New Mexico, Montana, Louisiana, and Kansas may share some similar conditions but have strikingly different geographies, with differing economic engines and assets, populations, cultural values, and origin stories.

Here’s one statistic that surprises most: While still economically and culturally important, agriculture now employs only about 5% of the rural workforce. Indeed, across rural America, it is services (professional, health, retail, social, tourism), manufacturing, energy, and the public sector that are the primary employers and increasingly important drivers of rural economies.2

Creative thinkers come from communities of different cultures and abilities — this diversity and engaging with underrepresented populations helps our placemaking be innovative.

Cheryal Hills, Region Five Development Commission

Rural America Is Growing – but That Growth Is Uneven

The too-conventional wisdom, repeated in the media and coffee shops, is that rural America is emptying out. The truth is that the US rural population has been fairly stable in recent years and has shown modest growth each of the last two years, from 2016-18.3 Another contributing factor: Many once-rural places have simply been reclassified as urban.4 And while the percentage of Americans who live in rural places has declined over time, the number of people living in rural America increased 11% from 1970-2010.5

Indeed, about half of our nation’s roughly 2000 rural counties grew in population from 2016-18. This has coincided with declining rural unemployment, rising incomes, and declining poverty since 2013.6 The rural places that are growing are typically those near metropolitan areas, those with abundant beauty and natural resources, those attracting retirees, and those employing immigrants. Some rural places are losing population, such as farming counties in the Great Plains and deeply poor counties in the South.7 But remarkably, every state

in our union has both some growing and some declining rural counties.

Rural America’s Population Profile Is Changing

While older and whiter than the nation as a whole, rural America is increasingly diverse. People of color comprise 21% of the rural population — but produced 83% of its growth between 2000 and 2010.8 Patterns vary across geographies, but job-seeking immigrants are a driving force behind recent rural population upturns: From 2010-2016, immigrants were responsible for 37% of overall rural population growth.9 Other analysis shows areas with a rural “brain gain” of people aged 30-49 and 50-64— age groups that tend to move to rural

for a simpler pace of life, safety, security, and lower housing cost.10 In a nation where cities are increasingly crowded and costly, rural places offer an affordable and high-quality alternative. Some rural communities have even launched recruitment campaigns for these age groups — and are succeeding.11

Economic, Social, and Health Outcomes Lag in Many Rural Places

The great variation from place to place in rural America includes economic, social, and health outcomes, which, on average, lag those of urban places, sometimes alarmingly so. Much of this has to do with poverty. Since the 1960s, when poverty rates were first officially recorded, the incidence of non-metro (rural) poverty has been consistently higher relative to metro (urban) poverty. The difference has narrowed, but it remains. In 2017, the rural poverty rate stood at 16.4% compared to urban at 12.9%.12 For children, the rural poverty rate was 22.8%, more than five points higher than urban’s 17.7%.13

The good news: The number of rural counties ERS designates as “persistent poverty” — those with 20% or higher poverty for the previous four decennial census counts — has declined since the 1950s. The bad news: Most rural counties where severe poverty persists are found in the Mississippi Delta, Appalachia, northern Maine, Indian Country, and colonias

(unincorporated rural communities along the US-Mexico border) — with a few exceptions, predominantly counties where people of color are the majority. Educational attainment and economic outcomes are also closely linked.

Recent data shows rural Americans are increasingly well-educated, with the portion of rural Americans holding at least a high school diploma on par with urban.14 However, between 2000 and 2014, the gap between rural (19%) and urban Americans (33%) with a bachelor’s degree or higher grew from 11 to 14 percentage points.15 At the same time, recent research documents rising rates of mortality and lower life expectancy in many rural places, particularly those with higher poverty rates and lower educational attainment.16 Not coincidentally, rural places with poor health outcomes also have the most stressed health delivery networks; more rural hospitals have closed in poor communities than in other rural places.17 In rural areas where opportunity is hard to come by, the opioid epidemic has taken hold, sowing chaos and deepening hopelessness. These rural places have captured the headlines and demand action and solutions. Even so, they do not reflect the full breadth of rural America’s conditions or experience.

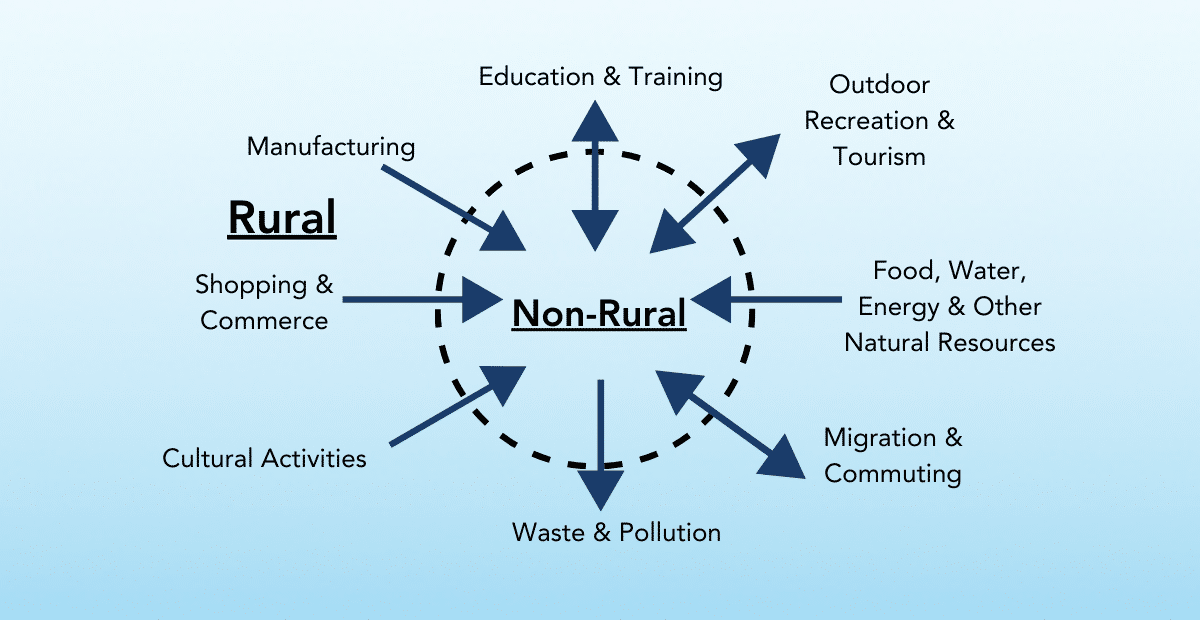

Rural and Urban Form Interdependent Regions

Most rural areas and nearby cities are entwined in relationships that define regions. But this relationship is not always realized or acknowledged, much less acted upon, and it can be as complex and varied as the rural landscape. Rural-urban ties can have one or more underpinnings: common geographic conditions such as watersheds or mountains; supply

chains that fuel industry sectors with services, goods, and talent; transportation and affordability-driven employee commuting patterns; media markets; and the need (or mission) to secure a share of essential goods and services (such as food and energy) locally. In some areas, rural places and cities are reliable partners and provide important markets for

each other. In others, intentional regional action is missing, and urban areas drain attention, energy, or resources away from surrounding rural locales.

Rural is Resource-Rich, Resilient, and Creative

Rural America has valuable assets, from water and natural resources to natural beauty, cultural capital, deep knowledge of place – and people with talent and resourcefulness. Some rural areas grapple with limited financial resources and acute infrastructure needs, such as antiquated water/wastewater systems or meager broadband. However, these constraints have also stimulated innovation and ingenuity in solving problems. The combination of few people, large geographies, challenges that extend across working landscapes (e.g., forest and watershed regions that span counties), and serious resource constraints can motivate collaboration across political boundaries. It can induce working together as partners, rather than as competitors, especially when there are too few resources to go it alone.

Endnotes

- Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. What is Rural? April 9, 2019. Link. ↩︎

- Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Rural America at a Glance 2017. Economic Information Bulletin 182. November 2017. Link. ↩︎

- Kenneth Johnson. Data Snapshot: Rural America Growing Again Due to Migration Gains. Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire. April 18, 2019. Link. ↩︎

- Andrew Van Dam. “The real (surprisingly comforting) reason rural America is doomed to decline.” The Washington Post. May 24, Link. ↩︎

- Benjamin Winchester. Rewriting the Rural Narrative. University of Minnesota Extension, Center for Community Vitality. 2014. Link. See also. ↩︎

- Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Rural America at a Glance 2018. Economic Information Bulletin 200. November 2018. Link. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Kenneth Johnson. “Where is ‘rural America,’ and what does it look like?” The Conversation. February 20, 2017. Link. ↩︎

- Kim Parker, et. al. What Unites and Divides Urban, Suburban and Rural Communities. Pew Research Center. May 22, 2018. Link. ↩︎

- Benjamin Winchester. Rewriting the Rural Narrative. ↩︎

- See, for example: Lisa Rathke, “Some Rural States Double Down on Attracting New Residents.” Associated Press. June 12, 2019. Link. See also: Jeff Yost, “What Rural Returners Are Telling Us.” Nebraska Community Foundation. January 30, 2019. Link. ↩︎

- Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Rural Poverty and Well-Being. March 25, 2019. Link. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Rural Education at a Glance 2017. Economic

Information Bulletin 171. April 2017. Link. ↩︎ - Anne Case and Angus Deaton. “Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century.” Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences of the United States of America. November 2, 2015. Link. ↩︎

- Sharita R. Thomas, George H. Pink and Kristin Reiter. Geographic Variation in the 2019 Risk of Financial Distress among Rural

Hospitals. Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. April 2019. Link. ↩︎

This blog is excerpted from the Rural Development Hubs: Strengthening America’s Rural Innovation Infrastructure report.

Copyright © 2019 by The Aspen Institute. All rights reserved.