Organizational capacity and technical assistance need to be carefully and intentionally strengthened in rural and Native nation communities to grow economies, health, and livelihoods for each and every person in their regions. So, how are rural organizations growing capacity?

On April 8, 2022, around 90 community and economic development practitioners and community members gathered at a Thrive Rural Open Field session to share tips, techniques, and resources to help build rural and Native nations’ capacity. This blog gathers those insights alongside related resources shared during our Rural Opportunity and Development session (ROAD) on the same topic and CSG’s often-referenced toolkit on Measuring Community Capacity.

“People live in communities. But the real importance of ‘living in community’ is that people—and groups of people—develop the ways and means to care for each other, to nurture the talents and leadership that enhance the quality of community life, and to tackle the problems that threaten the community and the opportunities that can help it.” – Aspen CSG toolkit on Measuring Community Capacity.

What is capacity and why is it important?

When we talk about capacity, the need for capacity-building or capacity-strengthening, we usually refer to communities and/or organizations. Community capacity is the combined influence of a community’s commitment, resources, and skills that can be deployed to build on community strengths and address community problems and opportunities.

Organizations also need capacity — particularly rural, native/tribal, and poverty-fighting organizations. One strategy often used to develop organizational capacity is technical assistance (TA). TA is help provided to a local organization or group of organizations by national or regional organizations, often using federal government resources. This typically involves sharing knowledge about available funding, connecting people to resources to reduce their cost-burden in the application process, grant-writing assistance, expertise in elements of the plans and other requirements in the funding application, and review feedback on the application itself.

However, technical assistance alone does not build organizational capacity – deeper and more durable investment is usually needed. Panelists at last year’s ROAD session framed capacity as the ongoing ability of an organization or community to accomplish the goals they set for themselves, rather than the ability to accomplish one particular project through technical assistance.

At its most basic level, an organization can achieve its goals if they have adequate and supported staff (and/or volunteers) with the resources, experience, and skills necessary to do the work to accomplish that goal. This includes the know-how to request and receive the right funding and technical assistance from external sources.

Here’s an example; say an organization has the goal of building a new community center. It needs local leaders with the ability to move the project from the earliest stages of community visioning to completion, and enough local and/or external funding to pay for construction – and potentially technical assistance from other organizations along the way to help train staff or fill in gaps in local know-how. Most importantly, the organization needs to have enough staff and/or volunteers, expertise, and resources at the beginning to convene all parts of the community to identify the need for and gain consensus on a community center before the building and fund development stages can begin. Easy to conceptualize, but putting it all together in many rural communities is daunting.

Here are strategies and tips discussed in our Open Field conversation that rural places, tribal communities, and Native nations use to make it happen. Read down the page, or use these handy links to jump to a section.

- Building capacity in rural and tribal communities requires trusting relationships built over time, not just at the project application stage

- Some rural places are growing their own local leaders to increase capacity, while others are relying on regional approaches to achieve goals

- National technical assistance programs should “walk-with” rural communities as they pursue goals

- Rural capacity resources (with links) shared by participants

- Quick and effective capacity-building tips from and for funders

- Five recommendations for government policy and practice that can lead to more rural and tribal capacity

Building Capacity, Building Trust

The first big lesson shared by Open Field participants is that fostering and maintaining trust is a key component of capacity building. Whether from the perspective of a local organization providing project transparency to the community, or a national technical assistance provider offering support to local community groups, trust among partners is often the secret sauce to achieving goals.

One trust-building strategy shared was to be there in person – if you are a funder, technical assistance provider, or government agency, visit the sites you are supporting. Talk and meet with local leaders and see their efforts in person to get insight into their challenges and opportunities. One participant shared that “[too] often, people from outside come in with good intentions while based in a city an hour away, and then leave, without longevity of thought or taking time, and not increasing [our] capacity. It has led to burn out for many in the community.” Investing time in a community means developing the cultural competency to see problems and issues from their perspective.

Cultural competency and trust is even more crucial when working with tribal communities and Native nations. One organization that helps Native entrepreneurs access capital while exploring and validating business ideas explained that “trust is the heart of everything that we do.” For this organization, trust is built by growing and maintaining three aspects: credibility, reliability, and intimacy. Credibility is knowing what you’re talking about; reliability is doing what you say you’re going to do; and intimacy is caring about others, their feelings, and well-being. These positive trust-building factors are influenced by self-orientation: having aligned goals and sharing a path. “We use it…to make sure that we’re being a trustworthy partner to our participants and to the tribes we work with.”

Building trust and cultural competency are also crucial when working with rural communities of color, historically disadvantaged, or persistently poor communities. To meet these communities where they are, participants voiced support for using trauma-informed practice.

A few participants shared their observation that well-intentioned community groups often want to build trusting relationships with new residents like immigrants and refugees. Still, too often, those communities’ needs are put second to the organization’s goals. To build trust, listen and support a community to make decisions and set goals for themselves, and put your own organization’s self-orientation on the backburner. and if that is not possible, then work on issues where organizational and community goals align. For more on how some of the best social service organizations build trust with immigrant and refugee communities, check out Aspen CSG’s new brief on this topic.

Grow Your Own and Regional Approaches

The second broad technique for building rural and tribal community capacity is a ‘grow your own” strategy that begins within the community. One participant noted that an organization needs to be self-sufficient to serve a community, meaning that local efforts must be realistic, strategic, and sustainable to grow over time.

Another participant shared their effort to grow their local leaders through a multi-stage, multi-year effort. This volunteer-led effort began by recruiting student interns from a local college, and through their help, they began recruiting paid AmeriCorps Vista employees. Through a pipeline of interns and Vista employees over seven years, the organization has developed the capacity to successfully apply for larger federal and state opportunities that have enhanced the community and grown the organization’s capacity.

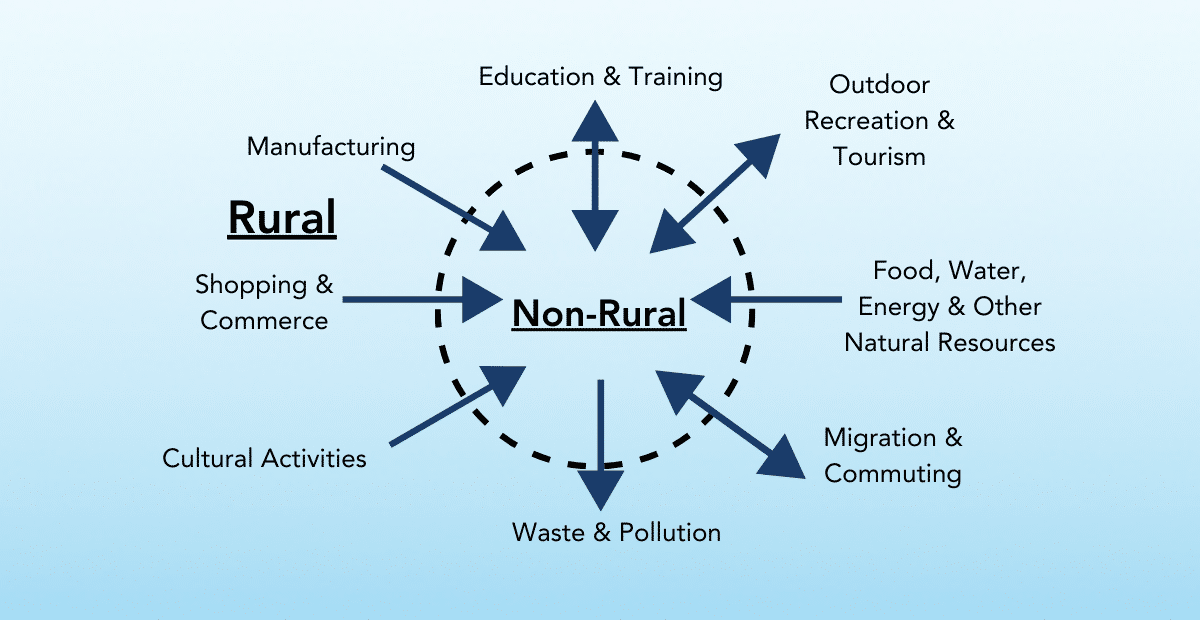

Often one rural community is too small to go it alone, and many Open Field participants voiced support for a regional approach to capacity building. Regional approaches often allow community groups and efforts to scale up and make a larger impact. A few participants shared the need to work with local community foundations or other rural development hubs in their region to take action on the community’s pressing issues. Community foundations and rural development hubs often have access to financial resources and the capacity to support community groups with financing or technical assistance.

Participants noted that working rural communities together on goals means that a competition mindset shifts to one of collaboration. But how to get started?

One participant suggested a regional approach to building capacity can begin simply with phone calls and virtual meetings among local leaders to find common ground and areas where collaboration is most feasible. Early wins like holding a public stakeholder group meeting can build valuable momentum on these efforts.

Participants highlighted that a crucial area for a collaborative regional approach to building capacity in drafting climate change and resiliency mitigation plans. A previous Open Field session highlighted the deep importance of beginning climate change and natural disaster planning as early as possible. While one rural community may be able to draft and implement plans to mitigate disaster, it’s more realistic to take a regional approach. This is applicable for hiring and supporting a grant writer to source planning funds. Because disasters are rarely localized – from hurricanes to wildfires to flooding, the scope of an affected area is usually regional, and planning must take that into account.

Technical Assistance that Walks With Rural Communities

Scaling up action is where a rural development hub can help. By sourcing resources from the national and state level and supporting local organizations on the ground doing the work, rural development hubs can play a valuable intermediary role. One participant from a rural development hub shared the perspective that for every potential project, the team at the hub asks the question, “do we row, or do we steer”? Rowing means doing the hard work of project implementation. In contrast, steering would imply another organization would be doing project implementation while the hub offered help like technical assistance and financing.

One participant noted that an organization that provides funding or technical assistance is not necessarily doing enough to build rural capacity. Securing funding for a project is often just the start, but rural communities also need support that “walks with rural communities through the implementation and administration of those funds.” A mutual, trusting relationship between assistance providers, funders, and those organizations receiving the help makes sure rural efforts can continue to build capacity and knowledge to secure funding in the future.

Participants shared that there continues to be a deep need for capacity funding and technical assistance for organizations that serve marginalized places. Too many rural communities have been historically marginalized because of race, place, and class. Due to the lack of external resources, organizations in those places tend to have lower capacity. Multiple participants shared that political polarization and the “good old boy” system are hard to overcome. External support, funding, and stronger capacity can mean the difference in changing the status quo.

How funders, including the government, measure success was also a big topic of conversation. Participants noted that grants and programs that measure success using quantitative outputs like jobs created or dollars invested put rural communities at a huge disadvantage when competing for funding. One participant asked the question, for small rural efforts, “how are we isolating the real value of the programs if someone’s capacity is less?” Another shared that nonprofits operating in rural areas need general operating funding that is not tied to measurable outcomes – but that funders continue to struggle with awarding this type of flexible resource.

Potentially Useful Rural Capacity Resources

Open Field participants shared many useful resources, links, and reports on building rural capacity during the session. The list below gathers them alongside a few others:

- In late April, the White House and USDA released the Rural Partners Network that will help identify challenges preventing rural communities from accessing federal support to inform the work of the Rural Prosperity Interagency Policy Council. This whole-of-government task force will ensure rural places are prioritized in Washington.

- The billions of dollars in funding made available through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law are great in theory but less helpful to rural communities that typically struggle to apply for and manage federal assistance. That’s where the White House’s new Rural Playbook comes in. The aim is to equip state, local, tribal, and territorial governments with information on the “what, when, where, and how to apply” for infrastructure funds. Most importantly, it includes a cost-share section that helps applicants find resources, reduce match requirements, and other important tools to reduce the cost of accessing federal funding.

- Though the deadlines for 2022 are rapidly approaching, consider going after Directed Spending Allocations for capacity building work now or in a future year. Rural organizations can work with their Senate or Congressional delegation to request project funding. These congressionally directed funds are not exempt from the requirements of federal grant programs. For example, an allocation for a Broadband project would be exempt from the competitive process for USDA funding but would need to comply with the regulations of the grant program. Open Field participants suggest those interested should connect with the agency that will be assisting with the project to be sure you understand the rules.

- AmeriCorps has created an Organization Assessment Tool that can help rural organizations acknowledge strengths, clarify different perceptions, and plan strategies to enhance capacity in identified areas. AmeriCorps also offers grants for Native Nations that can help tribal grantees build capacity.

- Aspen CSG’s recent Field Perspective brief on Native Nation Building shows that when tribes center sovereignty, Indigenous institutions, and culture in their development processes they increase the probability of reaching their goals and can build community wealth that is more in line with tribal values and lifeways. It also highlights how Native nations and rural communities together can grow thriving rural regions.

- The Western Governors’ Association is working to implement a ‘navigator’ to link communities and incident management teams/wildfire management. It is still a work in progress, but their website to learn more.

- A success story of capacity building funding comes from Power Up and Go in Kansas, a statewide effort to retain young families in rural Kansas.

- Region 5 Development Commission in Minnesota shared a handout focused on the Eight Forms of Capital and how this framework has helped organize their goals and frame their successes in building capacity in their region.

- Aspen CSG’s workbook on building rural capacity is an evergreen tool to help rural communities and leaders accomplish their prosperity goals.

- Mashup labs case study Virtual Business Incubator has a program that only runs in the evenings and typically at a time when support for child care from the extended family/community is more readily available. They believe this plays a big role in why 75% of their participants are women, over 50% of them with children 12-years and younger.

- Some state governments have a dedicated Office for Rural Prosperity that can help local organizations develop the capacity to engage on important issues. Kansas is one of these states. Their Office of Rural Prosperity advocates for and promotes rural Kansas and focuses on efforts designed to aid rural improvements, including holding Grassroots Economic Development 101 training sessions open for all organizations and groups to attend.

- Oregon’s Resource Assistance for Rural Environments Program works to increase the capacity of rural communities to improve their economic, social, and environmental conditions through the assistance of trained graduate-level members who live and work in communities for 11 months.

- The Delta Region Community Health Systems Development Program, funded by HRSA/Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, provides funding for hiring a Community Champion. The TA Center provides training, including facilitation skills, assessing community health needs, and collaboration opportunities.

- The Trust-Based Philanthropy Project offers resources and support to help advance equity, shift power, and build mutually accountable relationships between philanthropy and funded organizations.

- We have two additional links to recommendations that came out of the session for Philanthropy and for Government. Rural Capacity-Building Tips From and for Funders and Five Ways to Change Government Practices and Policy for Better Rural Capacity Results.

Hosted by Aspen CSG, Thrive Rural Open Field sessions are conversational gatherings where rural and tribal community and economic development professionals can meet and share stories and resources. Sign up for our newsletter to get information on our next Open Field session on June 10, focusing on rural environmental justice. Register here.