With a new administration in Washington, we can expect many proposals for shifting the direction of rural policy and programming. One of the first out of the gate is a bill from Senator Kirsten Gillibrand and Representative Antonio Delgado. They announced last month their proposed Rebuild Rural America Act of 2021. This would add $10 billion per year for five years to USDA Rural Development’s budget. The money would go to a new Rural Future Partnership Fund to be distributed to multi-jurisdiction Rural Partnership Councils in the form of block grants. The Fund would be the responsibility of a new Rural Innovation and Partnership Administration reporting to the Under Secretary for Rural Development. So how should we evaluate this proposal?

We must first acknowledge that any proposal adds to an already bewildering landscape of confusion, complexity, and ineffectiveness. A recent Brookings analysis of federally-funded rural development programs shows that rural communities must seek to access funding from more than 400 programs administered by 13 departments, 10 independent agencies and regional commissions, and over 50 offices and sub-agencies. Of these, 93 rural-exclusive programs in 13 agencies obligated $2.58 billion in grants and supported a loan portfolio of $38 billion in FY2019. The three largest sources of grant funding came from the U.S. Department of Agriculture ($1.06 billion), the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development’s Community Development Block Grant ($988 million for non-entitlement communities through state governments), and the U.S. Department of Transportation ($827 million). So, in sum, we have just $2.58 billion to meet the pressing development needs of up to 60 million people.

The Gillibrand-Delgado proposal describes a different vision for federal support for rural America. They talk about creating sufficient scale and capacity, in terms of funding and local institutional and community ability to use that funding effectively, to enable rural areas to achieve their preferred future. They see a leading role for rural America in addressing climate change and building a resilient nation, and highlight the importance of building on existing rural assets, promoting collaboration with neighboring areas and fostering connections between rural and urban areas. At the core is a national commitment to rural communities and regions based on comprehensive, collaborative and locally-driven community and economic development. It embraces the linkages between economic competitiveness and quality of life, and connects the dots between economic opportunity, workforce development, food systems, disaster recovery and mitigation, clean air and water, healthcare, housing and clean energy.

It is worth revisiting a set of five principles promoted by the Aspen Institute Community Strategies Group and Brookings for reimagining federal rural policy to assess this proposal, and indeed others that may soon emerge.

- Support local ownership and strategies, recognizing that rural communities must be the ones to own their transformation and to set their own strategies and priorities. The proposal places responsibility for developing plans in the hands of local Rural Partnership Councils that are intended to be representative of the full range of local rural community interests. As currently written, the proposal places few constraints on the nature of the strategies to be included other than that they should focus on economic opportunity, quality of life and resilience.

- Invest in people and institutions, building the capacity that is often lacking in rural communities, governments, and organizations to support investments in physical infrastructure and essential services. The proposal allocates $40 million a year to provide training, education, support and advice to Rural Partnership Councils, as well as a Rural Future Leadership Institute, and peer exchange programs.

- Increase flexibility and align federal and state funds to meet local needs, emphasizing the desirability of a “flex and align” approach that allows federal and state funding streams to support locally-defined priorities rather than some “one-size-fits-all” approach. It also stresses the need for longer-term investments rather than project-by-project support. The proposed Rural Partnership Plans are funded through five-year block grants to support a wide variety of local investments in critical infrastructure, basic public services, economic development and entrepreneurship, education and training, real estate development, housing, energy, arts and culture, and others. Unusually, the funds can be used to match and leverage support from other federal sources. The Rural Partnership Plans must be closely tied to existing plans required by other federal agencies, such as the Comprehensive Economic Development Strategies (CEDS), HUD Consolidated Plans, metropolitan and rural transportation plans, and the strategic plans of the Appalachian Regional Commission and other regional bodies.

- Measure and reward outcomes, expanding metrics beyond counting jobs or growth to measuring outcomes related to opportunity, quality of life, and equity. The proposal places responsibility on the local Rural Partnership Councils to define their own performance measures and reporting arrangements and to incorporate them into their Rural Partnership Plans for approval by the USDA. This presents an opportunity for the Fund’s overall metrics to be aligned directly with the Councils’ goals and strategies.

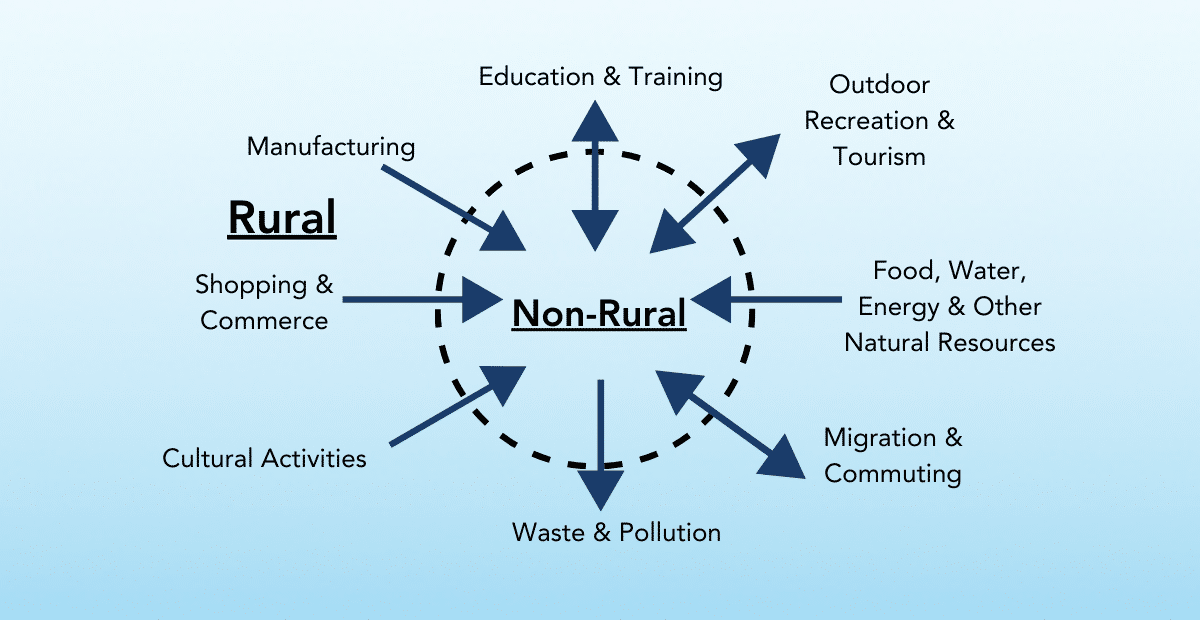

- Embrace a regional mindset, seeking connections with neighboring rural and urban communities, and seeing a rural future within a regional economy or system. The proposal places emphasis on regionalism and rural-urban connections by requiring Rural Partnership Councils to be based on micropolitan areas (or contiguous rural counties or Tribal reservations) and their Rural Partnership Plans to consider explicit linkages with surrounding jurisdictions.

To further explore the regional mindset aspect, I will add three more principles drawn from another Aspen Institute Community Strategies Group publication on equitable recovery and resilience.

- Support local leadership that is deeply rooted in the community and the region, widely trusted, and has the necessary capacity to understand and reflect local and regional historical, geographic, social and economic conditions. The proposal sees the Rural Partnership Councils as engaging units of government in the region, councils of government or regional planning councils, nonprofits, financial institutions, private entities, philanthropy, higher education, and many others. Although funding streams will most likely flow through local governments, there seems to be no obstacle for other types of institutions or organizations to assume the Council leadership role.

- Welcome voices to the table that were previously absent or ignored, ensuring that all community interests are heard and engaged to achieve greater geographic and racial equity. There is no explicit reference to equity and inclusion in the proposal as it stands. What we know is that without intentionality, equity will be hard to achieve.

- Healthy and sustainable economies and communities require the recognition that affordable housing, childcare, health care, workforce development, transportation, air quality and broadband are all interdependent and must be addressed as parts of regional ecosystems. The stated purposes of the Gillibrand-Delgado proposal are wide-ranging. They refer to climate change, resilience, economic integration and regional development, asset-based development, workforce development, technological change, food systems, land preservation, public health, healthcare, energy, housing and many other factors that will impact the rural future. As such, this is a rare opportunity to formulate plans that connect those dots in specific rural regions.

There is a lot to applaud in this legislative proposal. It is ambitious in scale and scope and accords well with most of the important principles for federal rural policy redesign, with the notable exception of its silence on the issue of equity.

The obvious questions are: Will this proposal see the light of day? And if it does, what will it look like after it has been through the legislative sausage machine? There are three issues to consider: the institutional arrangements, the scale, and the legislative design.

- Institutional arrangements: Who’s in Charge? The Gilllibrand-Delgado proposal calls for the creation of the Rural Innovation and Partnership Administration (RIPA), headed by an Administrator who will report to the Under Secretary for Rural Development at the USDA. The Administrator will be responsible for the Rural Future Partnership Fund that will disburse the block grants, provide technical assistance, maintain financial controls, and oversee performance. Much of the work will be assigned to new staff appointed to the rural development office in every state. A critical feature is the requirement to coordinate with a Council on Rural Community Innovation and Economic Development[1] intended to better coordinate Federal programs directed to rural communities and maximize the impact of Federal investment to promote economic prosperity and quality of life in rural communities. These arrangements appear to fall short of structures that could formulate an overall federal strategy for rural America and provide high-level oversight for coordination and integration of federal investments. They will thus depend for their effectiveness on the commitment and vision of the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture and the supportive engagement of multiple Senate and House Committees. Without these, the proposal will not achieve the desired outcomes.

- Scale: How Much Will Make A Difference? Clearly $10 billion per year for five years is a substantial commitment if it represents investments that are additional to existing funding streams and not a re-direction. Given the press of other demands on the federal budget, $50 billion will be a heavy lift, but it is commensurate with the scale of the problem and the ambition of the proposed legislation. There will be pressure to rationalize existing programs, which could be beneficial, but the danger could be a substantial scaling back of total funding, both for this proposal and for rural development more generally, to a point that the whole effort is reduced to yet another under-funded program with little chance of making an impact.

- Legislative Design: What Makes it Different and Innovative? It’s the combination of elements – longer-term block funding, locally-determined priorities and outcome measures, regional orientation, maximum flexibility, integration across federal agencies and funding streams, and connecting functions and systems – that make this a significant innovation in legislative design. Attempts to limit or remove any or all of these elements and bring them into line with conventional programming will inevitably reduce its effectiveness and impact.

The Gillibrand-Delgado proposal is a hopeful sign of thoughtful legislation that accords with many of our important principles for effective rural policy. It provides a clear vision and benchmarks; subsequent proposals should aspire to these and only improve upon them.

Brian Dabson is a Research Fellow at the School of Government, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and a consultant to the Aspen Institute Community Strategies Group and the Thrive Rural initiative.

[1] The Council on Rural Community Innovation and Economic Development would be the successor to the Interagency Task Force on Agriculture and Rural Prosperity established in 2017.