View this Publication

Use the side navigation bar to jump to different report sections. And don’t miss the related resources at the bottom of this page. Check out the Executive Summary for quick takeaways and actionable recommendations.

Introduction: Doing outdoor recreation development differently

In the wake of significant economic transformations, including industrial offshoring, energy transition, and the mechanization of agriculture, rural and Native nation communities across the US are looking at how they can use their plentiful natural assets to drive economic development and employment in their regions. Encouraged by federal programs and philanthropic initiatives, many communities are turning to outdoor recreation as a primary economic strategy.

Outdoor recreation economies can be an attractive option for rural communities seeking sustainable and stable alternatives to fluctuating and environmentally damaging industries like energy extraction. Additional advantages of outdoor recreation development are the health and wellbeing benefits for the local community. However, the tourism sector has a history of inequitable outcomes, including generating wealth primarily for outside investors, providing mostly low-wage and seasonal employment for local people, and putting unsustainable pressure on local systems and resources.

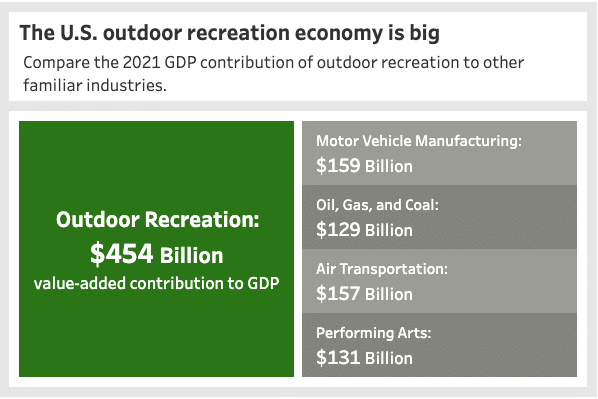

The outdoor recreation economy is one of the largest economic sectors in the United States, estimated at $374.3 billion in 2020, and recreation activities have a powerful impact on state and local tax revenue. While the COVID-19 pandemic has presented a major challenge for outdoor recreation communities, the rise of remote work and pent-up demand for vacation bode well for the sector’s future.

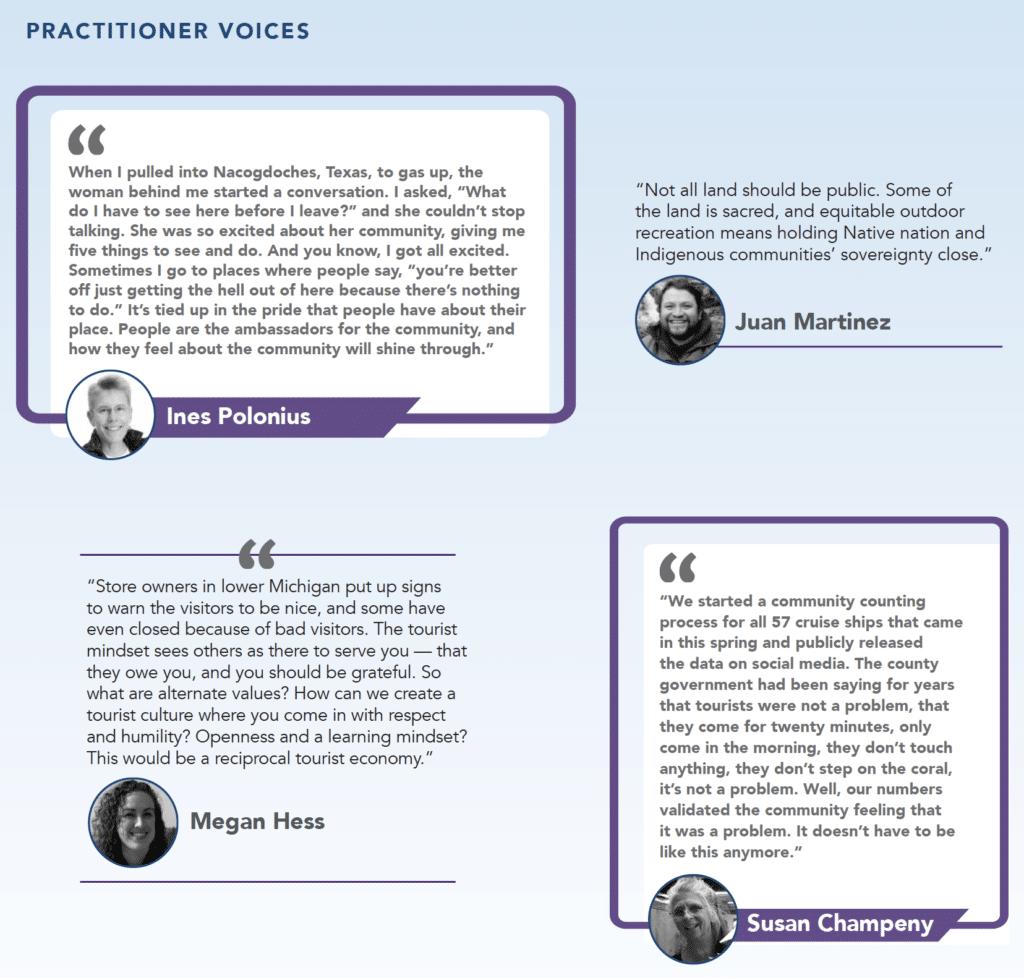

Rural and Native nation outdoor recreation communities have learned important lessons about the value of planning ahead to address these issues. For example, without plans or support for worker or community ownership options, local family businesses related to outdoor recreation are at risk of being sold to or controlled by outside interests. Without careful planning related to housing and transportation, outdoor recreation communities risk displacing workers and fixed-income residents (Aspen, Colorado, the original headquarters of Aspen Institute, has been profiled as an example of this challenge). And without careful attention to the overall impact of outdoor recreation development, destination communities risk becoming hollowed-out “showplaces,” designed to serve visitors rather than residents. This document amplifies the voices of rural thinkers and doers who have experienced these challenges on the ground and have valuable insights to share about how outdoor recreation can drive equitable rural prosperity.

As new rural outdoor recreation economies take root, we have the opportunity to meet this moment by improving the way we do outdoor recreation development to better support rural families, businesses, and workers, create more sustainable and equitable economic systems, and improve local health and wellbeing. At its most fundamental level, this means intentionally designing an outdoor recreation strategy that serves regional residents and tourists differently.

“Don’t just talk to elected officials. People in the community have ideas and deserve to be heard as well, especially when we’re talking about equity. In a lot of small towns, leadership isn’t exactly equitable, so we need to make sure that there’s representation in who we listen to.”

Stacy Thomas

Outdoor recreation development done equitably builds a sustainable economic strategy based on local and regional natural assets like forests, riverways, seashores, mountains, and more and connects those assets into value chains that grow local business ownership and high-quality jobs. Sustainability in this context means both a durable economy that avoids the boom and bust cycles all too common in rural places and an equitable economy that strengthens and preserves the diverse assets essential to the long-term health of rural communities.

“How can recreation create more jobs and local wealth for people in the community while not loving a place to death with overcrowding, loss of housing, or abuse of natural resources?”

Juan Martinez

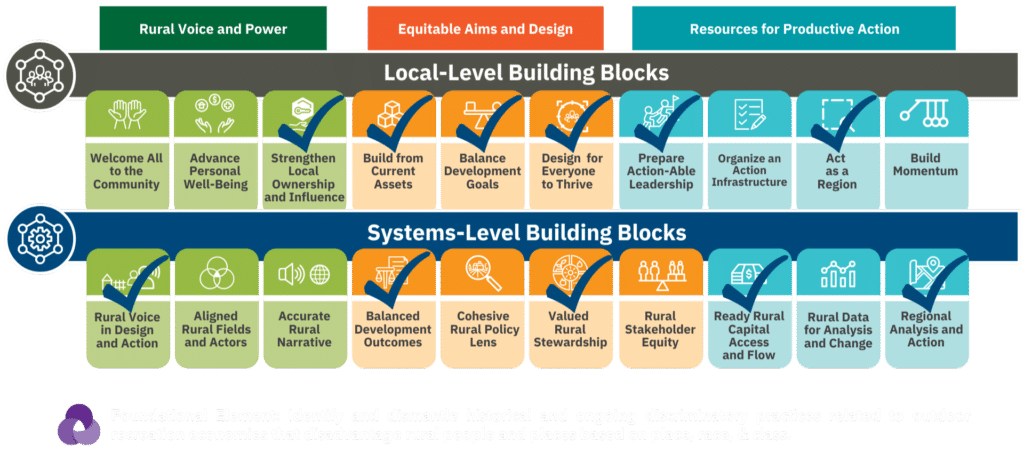

This Call to Action is part of a series that aims to equip local- and systems-level actors with equity-centered principles that will lead to equitable, healthy, and long-lasting regional economies in rural and Indigenous communities.

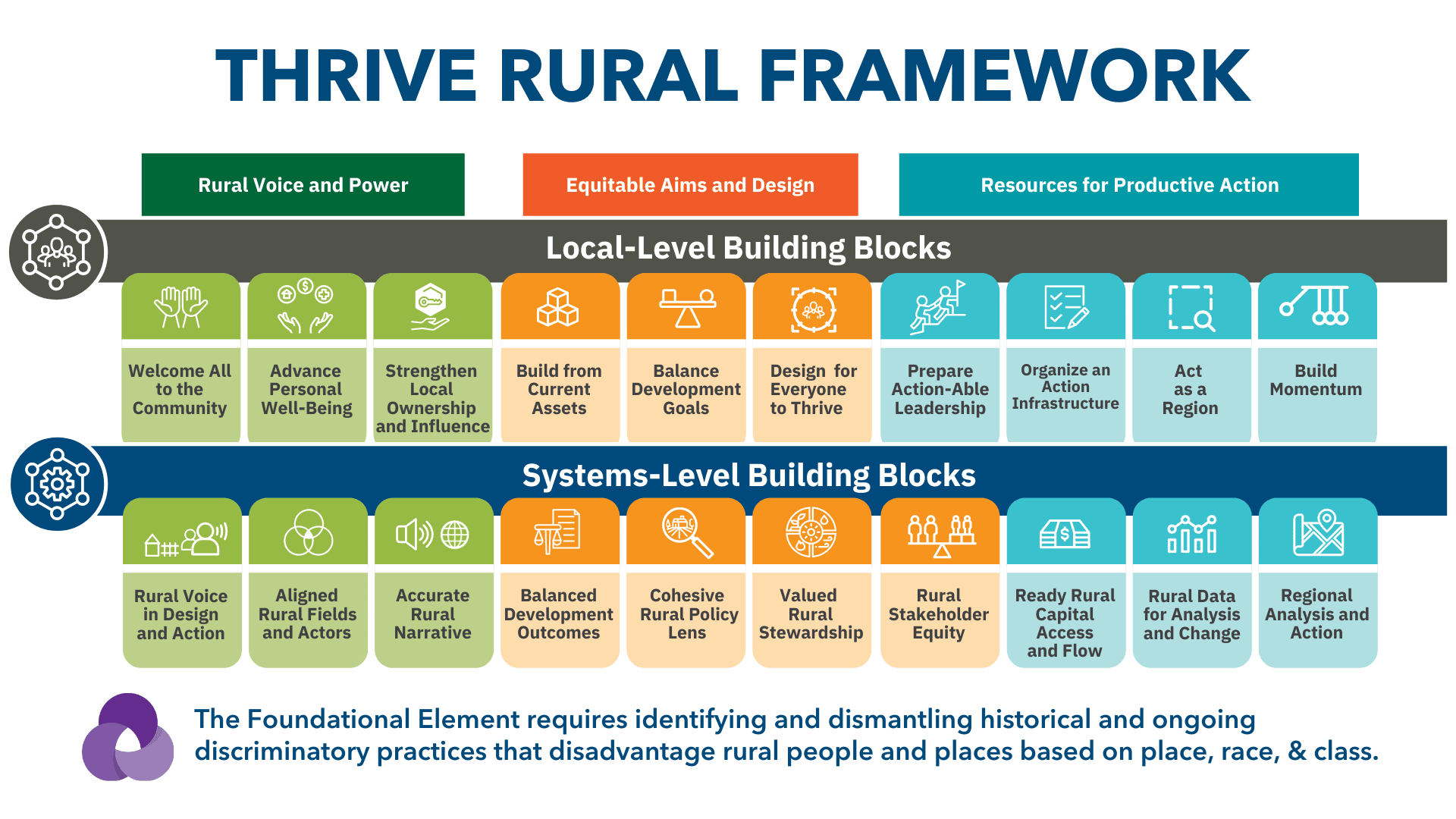

THRIVE RURAL

This Call to Action is part of Thrive Rural, which imagines a future where communities and Native nations across the rural United States are healthy places where each and every person belongs, lives with dignity, and thrives.

The Thrive Rural Framework provides both a shared vision and a line of sight into our current understanding of the local and systems conditions necessary to realize that vision — and this is true for tourism, outdoor recreation, and natural resource management. We’ve noted the most relevant framework building blocks from this Call to Action. Click the pages below to learn more about each of the highlighted building blocks.

Definitions

The definitions below are terms and concepts used regularly in this Call to Action. These definitions should not be considered exhaustive or final but act as a baseline for readers to understand the issues discussed in this document.

Equity: fairness and justice in outcomes and impact.

Equitable development: development activities undertaken with a focus on fair and just outcomes, especially for communities and people affected by historical and ongoing structural discrimination.

Equitable rural prosperity: the ultimate outcome of the Thrive Rural Framework — communities and Native nations across the rural United States are healthy places where each and every person belongs, lives with dignity, and thrives.

Outdoor recreation: all recreational activities undertaken for pleasure that occur outdoors (Bureau of Economic Analysis broad definition).

Region: an area involving multiple jurisdictions (e.g., counties, states) across which collaborative projects make sense for geographic, cultural, or other reasons.

Sustainability: the degree to which an economic activity is both durable, avoiding boom and bust cycles, and equitable, strengthening and preserving the diverse assets essential to the long-term health of rural communities.

Tourism: economic activity focused on providing accommodations, activities, and products to visitors.

Value chain: a WealthWorks value chain is a network of people, businesses, organizations, and agencies addressing a market opportunity to meet demand for specific products or services — advancing self-interest while building rooted local and regional wealth.

The TRALE Process: Structure and Participants

This Call to Action results from Aspen Institute Community Strategies Group (Aspen CSG)’s Thrive Rural Action-Learning Exchange (TRALE). TRALE is a process that quickly taps on-the-ground insights and experiences to help generate breakthrough thinking about what works and what’s needed to push rural policy and practice forward.

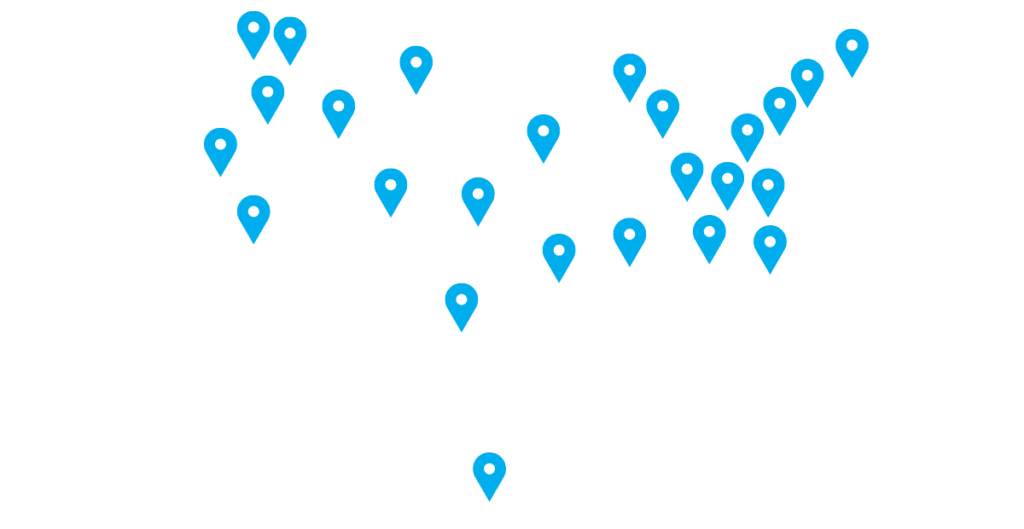

For this TRALE process, Aspen CSG convened 27 rural economic and community development practitioners from rural and Native nation communities across the United States. These rural practitioners, advocates, and innovators shared their experiences and ideas to answer the question, “What will it take for outdoor recreation economies to grow equitable rural prosperity?”

Collectively, the diverse participants account for a high level of experience and expertise in rural economic development, outdoor recreation, housing, transportation, small business development, family asset building, development finance, grassroots community engagement and advocacy, and regional development. They are respected, committed leaders in their communities, representing many regions of the United States, from the Pacific Islands to the Southeast. Click here for the list of TRALE participants.

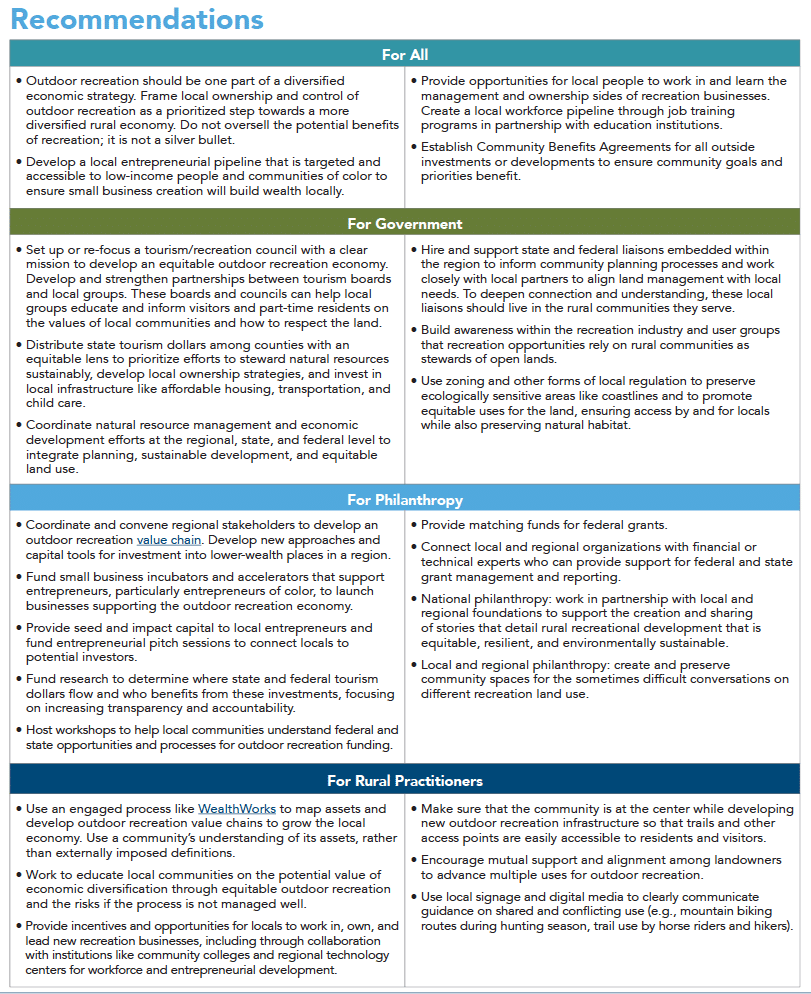

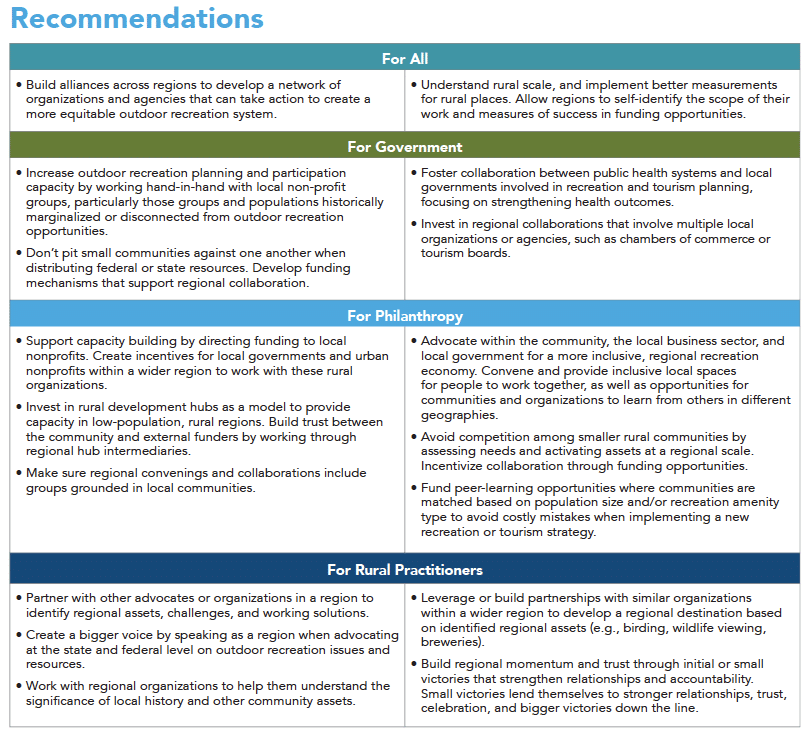

Cross-cutting Recommendations

As TRALE participants explored outdoor recreation economies as drivers of equitable rural prosperity — a future where communities and Native nations across the rural United States are healthy places where each and every person belongs, lives with dignity, and thrives — several overarching recommendations came up again and again. The cross-cutting recommendations apply to all five principles and all types of actors.

- Plan early to address and mitigate the community infrastructure challenges that can come with a successful outdoor recreation economy.

- Engage everyone within a community in project development, especially those whose voices are not usually at the center of outdoor recreation efforts.

- Support system-building to facilitate collaborative approaches to outdoor recreation challenges.

- Create learning and sharing networks among rural communities where solutions and challenges can be elevated and shared.

- Support leadership development and education to create the next generation of rural outdoor recreation leaders.

- Uplift and share stories of outdoor recreation development done well — in an equitable, resilient, and environmentally sustainable manner.

- Promote ongoing and deep cultural competency, equity, and justice discussions and workshops throughout communities within the region on an ongoing basis.

- Value Indigenous knowledge and experience in all planning, funding, and implementation processes.

- Read recommendations for other types of actors (e.g., government, philanthropy) to discover potential areas of collaboration and partnership in supporting this work.

“If we reframe Indigenous knowledge and see it as true scientific evidence made through rigorous testing over thousands of years and recognize the value of that knowledge practice the same way we recognize Western degrees, then we will have a huge economic shift.”

Janice Ikeda

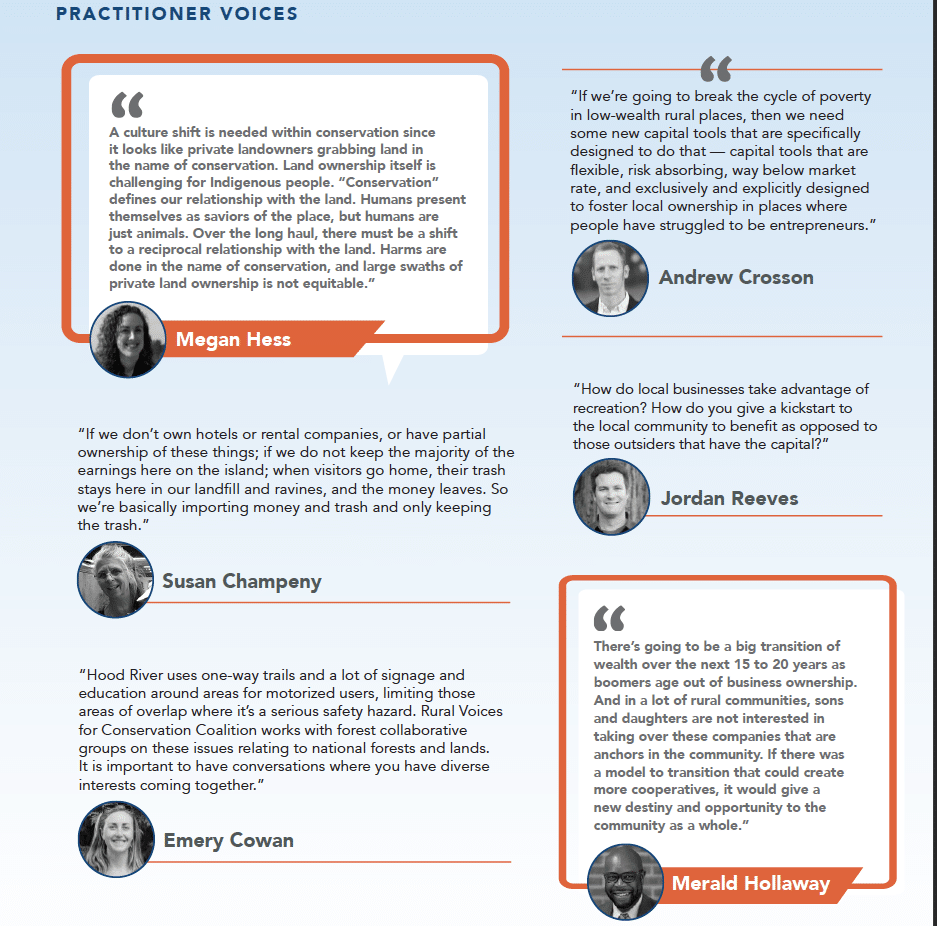

Principle #1: Advance local, equitable, sustainable ownership and control of outdoor recreation assets.

As rural communities move forward with economic development strategies based around developing outdoor recreation opportunities, front and center is the question of ownership and control of recreation assets like land, outfitters, restaurants, and hotels. Absentee ownership and control of assets contribute to “leakage” of funds from the local economy and introduce priorities from outside the region. An equitable development strategy prioritizes businesses, institutions, organizations, and resources critical to the outdoor recreation economy that are owned locally and/or directed and advised by the full range of community members who have a stake in their durability and success.

TRALE participants emphasized that local ownership keeps dollars circulating within the community, and equitable ownership of outdoor recreation assets allows more people to benefit from outdoor recreation activities, especially people who have faced economic exclusion. Key to growing more equitable ownership of assets and businesses is better and more equitable access to financial capital. Banks, CDFIs, and other lenders can do more to tailor their products to better serve rural recreation economy needs and to meet the needs of people not served or excluded by current systems. At the same time, philanthropy can provide collateral for loans, match for federal grants, and capacity-building operational grants that sustain non-profit organizations over time. Robust and multifaceted capital access enables local organizations, landowners, and entrepreneurs to develop new programming, businesses, and recreation opportunities owned and controlled by the community.

“The Verdi River in Arizona was at one point known as “the dirty Verdi” because of the polluted conditions. The community really wanted to turn that around, so they started promoting the river, and people became concerned about it. It was outdoor recreation that helped with conservation of the river — it also led to its own challenges of overuse, but they had a better way to talk about it than before.”

Omero Torres

Asset-based community and economic development strategies rest at the heart of an equitable outdoor recreation economy. Equitable recreation development should concentrate first on identifying and building on the area’s existing people, place, business, and organizational assets as a strategy to increase wellbeing and equity outcomes. Local and regional natural assets, from family-owned forests to public waterways, are the core building blocks for a recreation economy. Still, these natural assets must be developed and stewarded to provide recreational amenities that will attract visitors without overuse. Done right, an equitable and sustainable outdoor recreation economy preserves and protects working landscapes in a way that conserves and stewards them for future generations and for the health of the planet, while supporting people as they recreate and benefiting community member prosperity.

As noted in Principle 2, it is important to recognize that the successful development of an outdoor recreation economy leads to gentrifying pressures on housing and land as well as greater interest from outside capital in owning businesses in the community to profit from the location’s desirability. While the community may successfully develop and support locally owned businesses at the beginning, it is inevitable that owners may wish to sell over time as they retire or move on to new efforts. One important strategy to consider is to support the education and financing efforts that allow these businesses to become worker-owned cooperatives. This way, the control and wealth of these business efforts stay in the community over the long term, and wealth creation is shared even further.

“We must consider the long-term impact of land use, whether it’s recreation, agriculture, forestry, or climate change. Reports in the early 1960s said we needed to take measures to preserve the Salton Sea and yet we are still fighting for solutions to mitigate the health and environmental challenges the Sea presents. We must think differently. It’s critical to think: 100 years from now, what’s going to be the impact of decisions we make today?”

Roque Barros

Developing an equitable outdoor recreation economy relies on activating rural land and water assets by allowing visitors and residents to access recreation opportunities. Landowners, including government agencies, have different visions of what constitutes adequate access and shared use and may have biases towards or against one or more types of recreation use. For instance, private landowners may prioritize access to their land for hunting and fishing and resist calls to allow hiking, biking, or riding in certain seasons. Additionally, tensions over motorized and human-powered trail or waterway use can create conflicts within a community. Special care must be taken to build consensus on fair access and balanced use to prevent community animosity towards a recreation-based economic effort.

Outdoor recreation economies privilege the use of land and water assets for recreation, but rural regions use land for other economic activities as well, for instance, mineral extraction, forestry, agriculture, manufacturing, and, more recently, clean energy generation. A diversified and equitable recreation economy balances land and water use for recreation with other uses within a region. In many cases, equitable development of the recreation and tourism sector can be part of a solution to the decline in legacy sectors due to automation, offshoring, and other macroeconomic shifts.

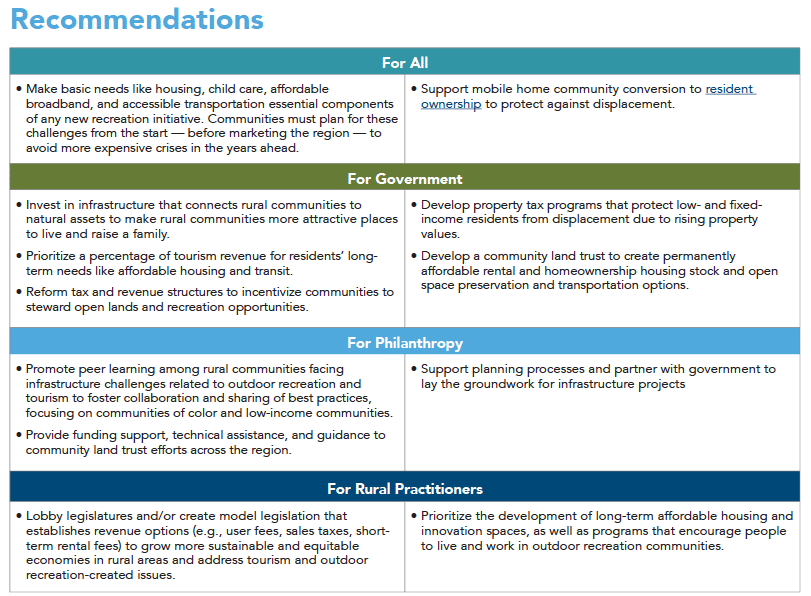

Principle #2: Build resilient infrastructure that supports a flourishing community, including diverse outdoor recreation businesses and workers.

Developing an equitable recreation economy requires centering the needs, voices, and perspectives of community residents. Too often, outdoor recreation infrastructure focuses on the needs of visitors or the promise of growth from outside interests rather than full-time residents. Building physical and community infrastructure to drive equitable rural prosperity necessitates a proactive and inclusive development process, planning for future growth and taking steps to avert challenges before they become intractable.

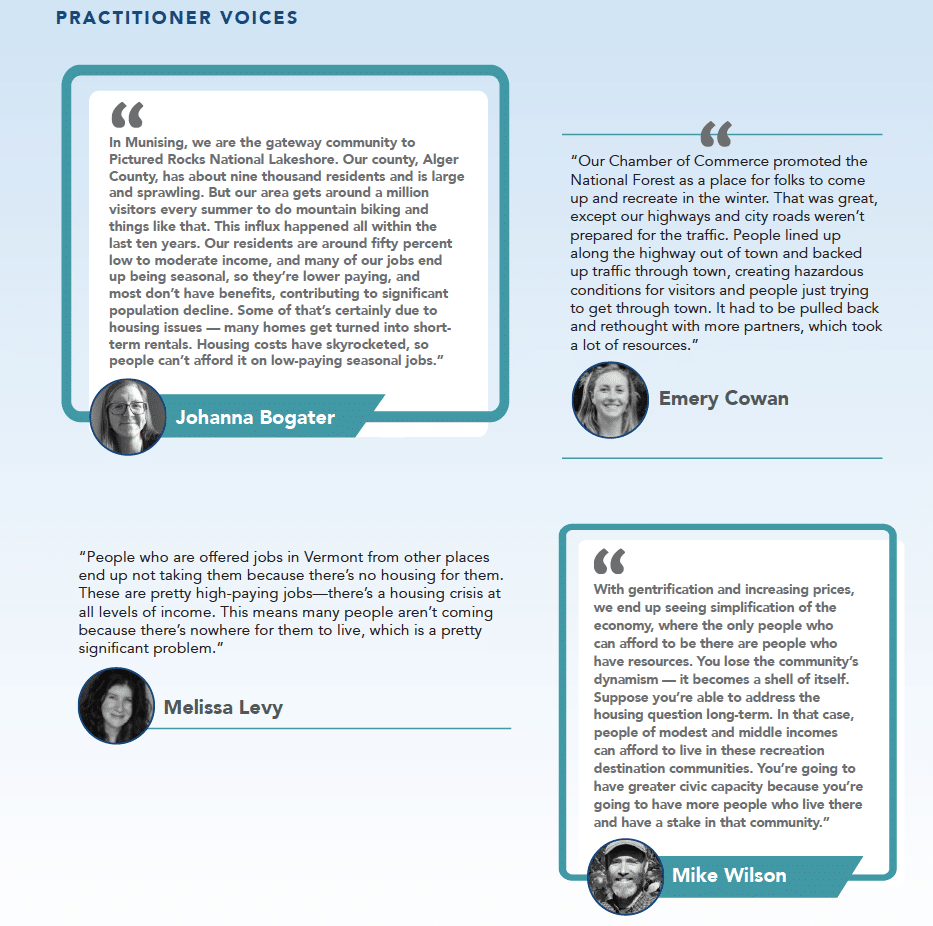

A sustainable local economy in any community requires a housing market affordable to the full workforce. While rural communities have historically been seen as inexpensive, today, far too many struggle to provide housing for their public and private sector workers as well as populations like seniors and persons with disabilities. Rural outdoor recreation economies can bring short-term visitors as well as second homeowners and retirees who want to live seasonally or year-round. This can put significant price pressure on land values and orient housing development towards these newer community members and visitors. Proactively addressing this issue requires intentional planning and preservation of existing affordable neighborhoods (including historically low-income and mobile home parks) as well as undeveloped land that can be utilized for long-term affordability (typically through a community land trust) from the beginning.

The short-term rental industry has put additional pressure on the rural housing market as homeowners shift to visitors rather than long-term tenants. These challenges can be especially pronounced in recreation communities. Developing new housing solutions rooted in local ownership and control (see Principle 1) from the onset — like rental housing financed by low-income housing tax credits and community land trusts to ensure long-term affordability — is vital for a sustainable and equitable local economy. No issue is more critical to success than thinking about housing. People may be able to commute from outside the community for a time, but successful growth will quickly gentrify local and regional housing prices that result in major labor and quality-of-life challenges down the road.

“When I hear “outdoor recreation economy,” I immediately think of the people who support those economies, and it’s often seasonal workers. And when I think of seasonal workers, housing is what always pops up. I most recently came from working for Idaho state parks, and I had a commute of about 40 miles one way because there wasn’t housing in the tiny ranching community. Often, a very privileged few could accept that position, someone who had a van that they could live out of or a trailer that their car could pull. Some people were up for camping in a tent for five months, but in the West, we can have snow in June, and we can have hundred-degree days. So appropriate, safe, comfortable housing for workers ultimately is about equity and our economies and how they can sustain this kind of increased recreation use.”

Kate Yeater

“Part of the problem with many of the attempts to develop affordable workforce housing has been that as soon as it gets in the market, people cash out their equity, and it becomes unaffordable. If you can keep the ownership of the land separate from the occupancy of the unit, and you have some rules about who can buy it, you can minimize price inflation. So there are models that work, but you have to take the ability to cash out the equity in a high amenity place out of the equation for sustainable workforce housing.”

John Molinaro

Because rural outdoor recreation regions tend to be large with limited roadways, quality transportation infrastructure is important for visitors, long-term residents, and workers. Well-designed highway and road connectivity, public transit, and multi-modal transportation options (especially planning for safe bicycle use) allow visitors to move safely from their accommodations to recreation areas and permit residents and visitors access to local services like grocery stores and health systems. Given that most rural development has been linked to road widening as a strategy, establishing local transit networks that can move workers and visitors to recreation amenities is vital for the long-term sustainability of a community. As with other infrastructure types, failure to plan and intervene at the start leads to much more expensive solutions later on, as well as real workforce challenges as commuting and traffic congestion become major issues to resolve.

Broadband internet connectivity is also essential infrastructure for rural recreation economies, especially in facilitating local business development. Given the rise of remote work, many prospective visitors and residents require high-quality connectivity, and communities are working hard to access federal funds to build out networks. As with the other forms of infrastructure discussed above, broadband should be designed for the full spectrum of local residents, not just visitors. To drive local prosperity, newly built networks should be accessible, reliable, and affordable to all, not just in the short term.

Finally, the importance of child care as infrastructure is rarely realized in rural places until it becomes a crisis. Developing an outdoor recreation economy typically leads to several retail, restaurant, and hotel businesses, not to mention other service economy elements. These jobs rely on a range of hours for operation and typically are not high-wage employment that would support a single-wage-earner household. Given these demands, flexible, affordable, quality child care is a critical element of community infrastructure that needs to be organized, developed, and supported. This requires links to job training and small business programs, facilitating certification programs, and connection to other statewide resources that can help support a local/regional child care community.

Principle #3: Work regionally to build trust, achieve scale, and meet shared outdoor recreation challenges and opportunities.

The development of rural outdoor recreation economies relies on coordinating assets and stakeholder engagement at a regional level. Recreation economies are always regional economies because of the scale of recreation assets — waterways, mountains, and forests don’t begin or end at the jurisdictional boundaries of townships or counties. Stewarding natural assets to develop equitable recreation opportunities can mean crossing counties and building consensus, sometimes within a multi-state region. Acting as a region allows different localities to persistently analyze, develop strategies, and act together within and across sensible and workable regions to address shared issues, challenges, and opportunities and achieve outdoor recreation outcomes at a productive scale.

Rural Development Hubs are the main players in rural America that are doing development differently. Hubs think of their job as identifying and connecting community assets to market demand to build lasting livelihoods, always including marginalized people, places, and firms in both the action and the benefits. They focus on all the critical ingredients that either expand or impede prosperity in a region — the people, the businesses, the local institutions and partnerships, and the range of natural, built, cultural, intellectual, social, political, and financial resources. They work to strengthen these critical components and weave them into a system that advances enduring prosperity for all.

Hubs play a transformative role in their regions and communities. They are not focused on meeting immediate needs alone. They also aim for and deploy systemic and long-term interventions and investments to strengthen the essential components that form a better foundation for lasting prosperity.

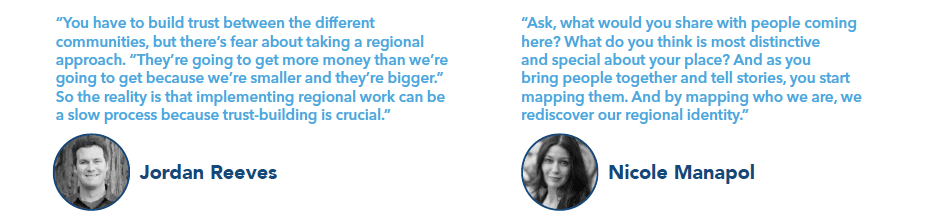

Working together across a region, this approach requires that parties, organizations, leaders, and communities develop trust. Trusting relationships make regional coordination possible because communities acting alone may fall into a competitive “race to the bottom” trap to attract recreation businesses or opportunities, undermining each other’s efforts in the process. Many rural communities are too small to go it alone on economic development. Rural regions can develop the scale necessary for more equitable prosperity by collaborating and coordinating across a wider geography.

The trust necessary to work as a region is built step-by-step through listening and understanding diverse stakeholders’ needs, values, and concerns and incorporating those perspectives into plans and action around outdoor recreation. Trusting relationships and regional coordination allow multiple governments and private-sector units like recreation planning councils, chambers of commerce, or tourism bureaus to develop comprehensive strategies or plans that help map out opportunities for recreation development that are inclusive of the whole region.

Coordinated regional action to plan and build an outdoor recreation economy increases the likelihood that collaborations and intermediary organizations like rural development hubs will apply for and win federal, state, and philanthropic funding designed to help grow the region’s economy. Through coordinated hub action, regions are more likely to secure investments or incentives to address shared cross-community economic, social, and health challenges and opportunities.

Convening for the Recreation Economy

The Niel and Louise Tillotson Fund at the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation is a rural philanthropy dedicated to economic opportunity. Since their founding, the Tillotson Fund has played a rural development hub role by funding economic development projects in the Northern Forest. This region stretches from New York’s Adirondack Mountains to the northern border of Maine. Their work includes grants to the Conservation Fund and Appalachian Mountain Club to support in-depth analyses of demand for outdoor recreation, barriers to recreation industry growth, and opportunities to inspire entrepreneurship and growth in the outdoor sector. Regional foundations like the Tillotson Fund can be instrumental in convening regional stakeholders to start a conversation about building a regional network and strategy. Managing relationships and building trust takes time, and philanthropy is well-positioned to play this convening role in the outdoor recreation system.

“Philanthropy, especially small regional foundations, can be instrumental in bringing all the necessary folks together to start the conversation around equitable outdoor recreation. An intermediary of that kind convenes and provides the funding to do market research to see if there is demand. It takes time and money to bring people together effectively, so that’s a big role for community philanthropy.”

Melissa Levy

“Don’t pit small communities against each other. Instead, encourage them to come in together on a grant. Funders shouldn’t make it too prescriptive. Every landscape is different. To make it work, a program or grant has to be specific to a rural place, considering its culture, needs, and assets.”

Ta Enos

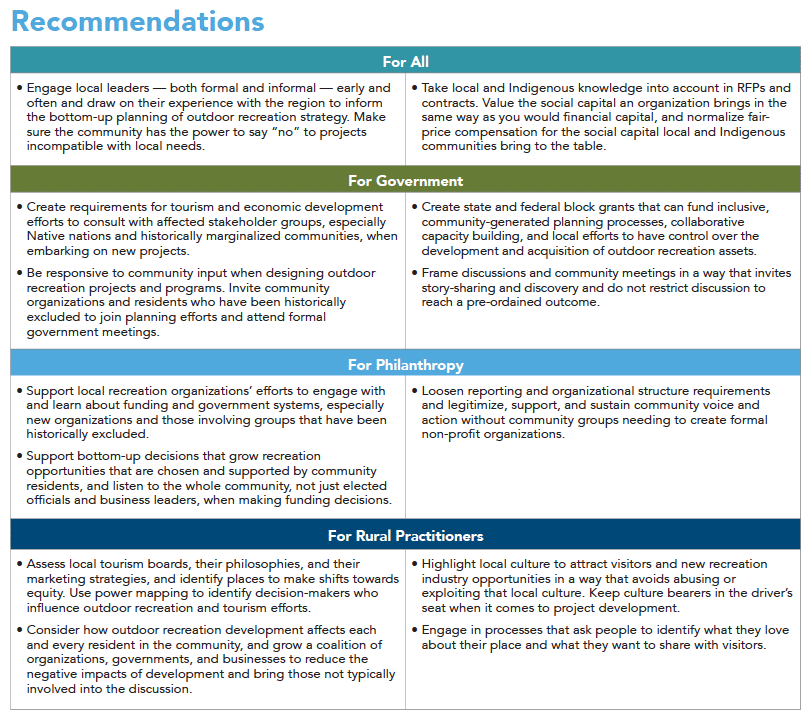

Principle #4: Respect the local landscape, people, and culture in the design and implementation of all development efforts.

Respect for the local landscape, people, and culture is a foundational element of an equitable outdoor recreation economy. But a balanced, respectful relationship is only possible where all participants enter the relationship voluntarily and with the power to shape the interaction.

There is a dramatic difference between sharing a culture and place on one’s own terms and the exploitation of a culture and place by outside forces. That difference is who has the power, who shapes the interaction, and who benefits. Too often, tourism and recreation economies are based on the exploitation of a people, culture, and place for outside profit. To avoid this, local people from across the community must be active in designing visitor infrastructure and activities — which includes the ability to say “no” to new activities or projects that would be destructive or incompatible with the health or self-respect of the community. This is particularly important to consider in communities with a history of power imbalance or exploitation, including Indigenous communities, Black and immigrant communities, and low-wealth communities.

Indigenous communities seeking to reestablish balanced use of land in ways that honor ancestral connections as well as preserve the health of the land for future generations may experience special challenges regarding respectful use of land for tourism and recreation. An economic model that only sees land as a resource to be used for human recreation desires is incompatible with these goals. Private ownership models can also challenge community access to ancestral lands and cultural activities. As a path forward, some Indigenous communities are promoting regenerative tourism as a way to invite visitors to recreate and give back to the land and community at the same time.

The Potential of Regenerative Tourism

“Regenerative tourism means shifting from an extractive relationship to investment and reciprocity. It starts with an awareness of belonging, and from that sense of belonging to that place and community grows what we call kuleana (responsibility, seen as a privilege). It means the aloha spirit, the way of welcoming a person to feel a sense of belonging that translates into a deep sense of responsibility to that place. The joke is, you know you are family if you are invited to a home for dinner, and they let you wash dishes. One indicator of regenerative tourism is the willingness to move from the dining table to washing dishes. The willingness to reframe and question everything we’ve been told is knowledge, success, wealth. It is a low bar to just focus on sustainability. In the past, Hawai’i wasn’t just sustainable, it was abundant.” – Janice Ikeda

TRALE participants shared the many challenges rural communities face regarding disrespectful and destructive behavior by tourists and visitors, from Maine to Hawaii. But they also shared the challenges local people face in sharing their communities with pride. “Why would anyone want to come here?” is a common reaction to the possibility of a recreation economy in places that haven’t historically been seen as valuable or special. Both of these challenges have the same roots: pride of place and self-respect are only possible when local people have power and voice, and disrespectful systems evolve where that power and voice are lacking.

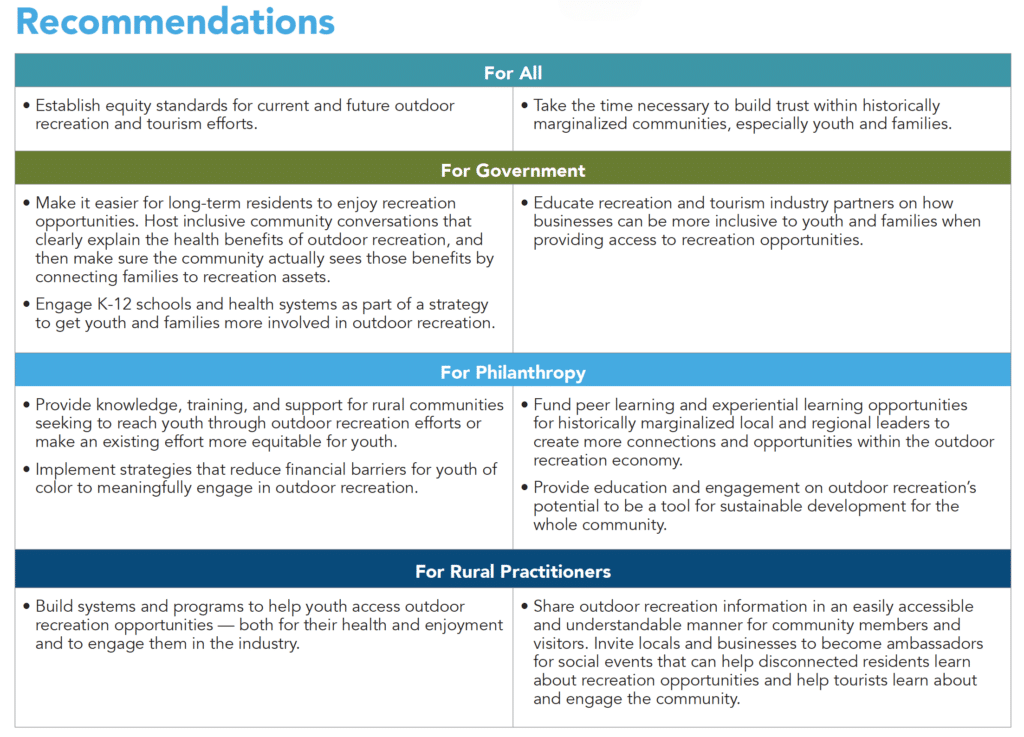

Principle #5: Design for equitable access to and participation in outdoor recreation activities.

Given our country’s historical and existing exclusion of people from political power, social mobility, and economic opportunity based on the location or size of their community; racial, immigrant, or cultural identity; or wealth or income level, it should not come as a surprise that different demographic groups have varied levels of participation in outdoor recreation.

Youth, particularly youth of color, are less likely to take advantage of outdoor recreation, which means they are missing from the outdoor recreation economy as consumers and potential business owners or workers. And the high cost of recreation activities — from gear to entry fees — means that people and families without the financial means to participate are also missing from the outdoor recreation economy. As a result, youth and low-income people are less likely to enjoy the vital health and mental health benefits of being active outdoors.

Equitable access to recreation activities and opportunities requires the intentional design of efforts, including voices beyond the overwhelmingly white and affluent population that currently recreates. There is a genuine risk that developing new outdoor recreation economies will reinforce or deepen existing economic, health, and social inequities in rural communities. In every aspect of planning, design, funding, development, and implementation of outdoor recreation economies, governments, philanthropy, practitioners, and community members must actively consider who is at the table, who will benefit, and who will have access to opportunities and programming.

Done right, an outdoor recreation economy designed for the whole community as well as visitors has the potential to spur local wealth creation through entrepreneurship, drive local ownership (see Principle 1), and provide opportunities for young people to stay in their communities and thrive.

Getting to Know the River

The beautiful and awe-inspiring lower Mississippi River is often inaccessible to people who live nearby, due to physical barriers like levees, or social and economic barriers to recreation access in the region’s low-income and majority Black communities. The Lower Mississippi River Foundation helps local youth get to know the river through outdoor recreation programming, including exploration and camping trips that develop wilderness skills and introduce participants to outdoor recreation. The Foundation aims to build connections between young people and the river so that future generations will love, protect, and value it.

List of TRALE Participants

Roque Barros, Executive Director, Imperial Valley Wellness Foundation, California

Alex Biswas, Strategic Partnerships Manager, The Wilderness Society, Washington

Johanna Bogater, Northern Michigan Organizer, We The People, Michigan

Susan Champeny, Artist and Wai’uli We Count Project Coordinator, Hawaii

Emery Cowan, Program Manager, Rural Voices for Conservation Coalition, Colorado

Andrew Crosson, CEO, Invest Appalachia, North Carolina

Ernestor De La Rosa, Chief Diversity Equity and Inclusion Officer, City of Topeka, Kansas

Ta Enos, Founder and CEO, PA Wilds Center Entrepreneurship, Pennsylvania

Sabrina Golling, Partnership Manager, MDC Rural Forward, North Carolina

Megan Hess, Rural Organizing Director, We the People, Michigan

Merald Holloway, Founder, NC 100, North Carolina

Janice Ikeda, Executive Director, Vibrant Hawai’i, Hawaii

Whitney Kimball Coe, Director of National Programs and Coordinator of the National Rural Assembly, Center for Rural Strategies, Tennessee

Melissa Levy, Principal and Owner, Community Roots, Vermont

Katie B. Luna, President, The Chamber of Commerce for Great Calexico, California

Nicole Manapol, Community and Economic Development Specialist, Rural Community Assistance Partnership, New York

Juan Martinez, Senior Program Manager, Aspen Institute Forum for Community Solutions, Texas

John Molinaro, Principal, RES Associates LLC, Ohio

Hetal Patel, Program Manager, MDC Rural Forward, North Carolina

Ines Polonius, CEO, Communities Unlimited, Arkansas

Oak Rankin, Executive Director, Glacier Peak Institute, Washington

Jordan Reeves, Rural Communities Director, The Wilderness Society, Montana

Stacy Thomas, Community Coaching Programs Coordinator, West Virginia Community Development Hub, West Virginia

Omero Torres, Recreation, Heritage, Lands, Minerals, & Partnerships Staff Officer, U.S. Forest Service, Oregon

Nancy Van Milligen, President and CEO, Community Foundation of Greater Dubuque, Iowa

Mike Wilson, Senior Program Director, Northern Forest Center, Maine

Kate Yeater, Outdoor Education and Trails Stewardship Coordinator, Salmon Valley Stewardship, Idaho

Support for this report was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Ford Foundation. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundations.

Related Resources

Related Aspen CSG Products

The following people worked together to shape this Call to Action:

- Action-Learning Exchanges were facilitated by Bonita Robertson-Hardy and Chris Estes, with coordination

support from Tyler Bowders. - Devin Deaton identified key themes and highlighted participant quotes and stories.

- Aspen CSG’s consultant Rebecca Huenink led the writing process.

- The entire Aspen CSG team – Bonita Robertson-Hardy, Chris Estes, Erin Cahill, Devin Deaton, and Tyler

Bowders – helped edit and sharpen the concepts.