Rural and Native communities have been stewarding the land for generations. Many are using new ways of growing nature and the economy together, even as negligent and extractive industries and chronic underinvestment have made stewardship a challenge.

On May 13, 2022, over 50 rural community practitioners gathered at an Open Field session to share how they are thinking and acting on rural stewardship, including how they are working to balance their region’s economic development with environmental sustainability. This blog curates the themes, ideas, and resources shared by participants.

This discussion was grounded in Aspen CSG’s Thrive Rural Framework. Based on research and best practices from the field, this framework shows what needs to be true within both a local-level and systems-level theory of change for equitable rural prosperity to occur. Read more about how the Thrive Rural Framework features stewardship as an important component of equitable rural prosperity.

These helpful links will jump you down into different sections of the blog:

- What is Rural Stewardship?

- Perspectives on Landscape

- Valuing Rural Stewardship

- Balancing Rural Tourism

- Rural Stewardship Resources

What is Rural Stewardship?

Chitra Kumar and Mikki Sager, authors of the latest brief in Aspen CSG’s Field Perspective Series on Stewardship + Equity, grounded the discussion with their definition of rural stewardship:

We call patient, steady, and creative care for our natural resources – so that resources are both productive today and last for future generations – stewardship. Rural and Native people and communities have been doing the work of stewarding for all of us for centuries.

Practitioners confirmed that rural stewardship is a valuable way to frame decision-making and action that supports both the economy and the natural environment. Yet it is important to remember that because of the nuances and contexts of rural communities, stewardship often looks different in different communities.

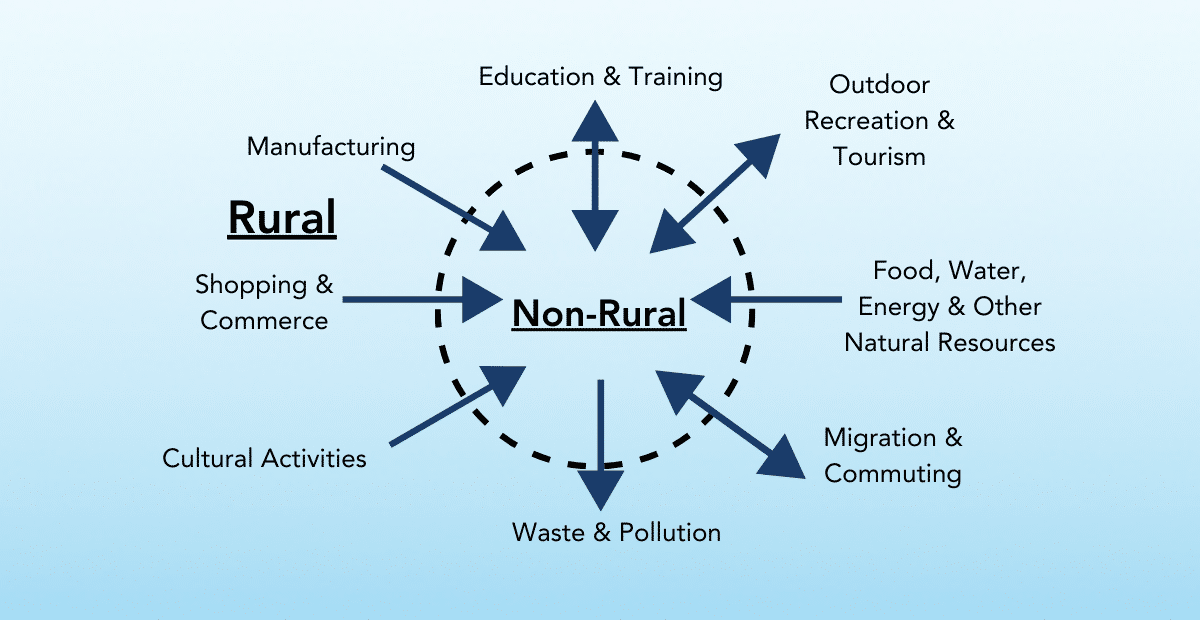

There was common agreement around two related facets of rural stewardship. First, the development goals for a rural community or region must be balanced to consider the health of natural ecosystems and watersheds. Balanced development goals support both a current community’s needs and sustain the community and natural systems well into the future. Second, the participants voiced that success in the system-wide outcomes of development should be measured by reducing poverty and racial inequality and increasing natural capital and the health of the landscape.

Perspectives on Landscape

The different ways rural people relate to natural landscapes were front and center during the discussion. The principal productive tension was between a view of the land as a natural resource to be sustainability used for the betterment of human communities and a perspective voiced primarily (but not exclusively) by Indigenous participants that that land is an intrinsic part of the wider community, much like a family member, and not a resource to be exploited.

Economic development based on the commodification of land is at odds with many Indigenous traditions. Attendees from Native nations emphasized that American communities, both rural and urban, are living on stolen land and governed by broken covenants. From this perspective, what is needed for landscape stewardship is a decolonization of thinking and doing and the embrace of Indigenous traditions with their 40,000 years of experience sustainably working with the land and operating via bartering systems. One participant called this way of thinking and acting Indigenous regenerative intelligence.

Another aspect of the discussion was the tension between the system boundaries found in nature like watersheds – a geographic area united by river drainage – and system boundaries determined by humans – political jurisdictions like towns or counties. Ecosystem issues like flooding or drought pay no attention to political jurisdiction, but the communities tackling those problems must. Participants shared the frustration that working on landscape stewardship issues often necessitates working across political jurisdictions, adding another layer of complexity to finding successful solutions.

Valuing Rural Stewardship

Rural places are home to a wealth of natural resources, and much of the discussion centered around how to sustainably balance the economics of resource extraction. Some participants shared that while there are intense global demands for commodities like copper or wood products, citing new mines and factories in certain communities is difficult because of legal challenges. Conflict over the use of the land can stymie economic development and spur political polarization, potentially exacerbating divides and making collaboration and progress even more difficult.

One example of a region that has successfully bridged political divides and charted a course for economic prosperity and ecosystem health comes from Blue Mountain Forest Partners. Eastern Oregon was the epicenter of the “timber wars” of the 1990s. Today, the region is home to a collaborative partnership among Native nations, environmental organizations, government, private landowners, and timber companies that are fostering equitable rural prosperity and land stewardship. You can dive deep into their experience and lessons through a blog and event recording from Aspen CSG and an article about the effort published in the New York Times.

The core issue for many participants was that global economic systems and stakeholders do not value rural stewardship and have not adequately compensated rural communities for the natural resources they have or plan to extract. Nor have these systems prioritized the health of the land and the prosperity of rural and Indigenous communities that rely on that land.

A major goal voiced during the session was that the benefits of natural resource extraction must accrue to the community, not only to external stakeholders. Participants suggested that development projects like mines or wood products factories are more likely to succeed in this goal if decisions are made in a collaborative way that engages all affected stakeholders and members of the region to fully address the needs, issues, and values of the wider community.

Balancing Rural Tourism

Rural places are home to stunning vistas, hiking, boating, and other outdoor recreation opportunities, and in recent years, tourism has grown in popularity as a rural development technique. The vibrant discussion of tourism suggests that many rural communities are trying to reinvent local economies in a way that incorporates the history of the region. Participants shared many perspectives related to the value of tourism for rural economies, but one thing was clear: the benefits of a tourism economy must support all community residents through high-paying jobs and related opportunities without damaging the landscape.

Rural tourism leverages local and regional assets to attract visitors who spend money at local businesses. One participant offered the perspective that revitalizing a community through tourism creates a fragile basis for prosperity since the jobs created by a tourism economy are usually low-wage, without benefits, and often seasonal.

The risk is that tourism money doesn’t stick within the community, and workers can’t afford to patronize the businesses where they work. Instead, participants suggested growing prosperity from the ground up by fostering entrepreneurship and cooperative or employee-owned business opportunities. and by only recruiting new businesses that will respect the local environment, value the land, and recognize the history and traditions of the region.

One participant suggested using worker training to educate servers and hospitality workers about the economic opportunities available in their community. Another technique offered by a participant from Minnesota was for local and regional development agencies (including CDFIs) to direct their grants, loans, and tax credits to businesses and development efforts that embrace community tradition and value the land.

The stories of balanced tourism economies shared during the session all relied on deep collaboration. For example, one participant related how the tourism economy of their region in Eastern Tennessee is growing through partnerships between regional economic development councils and poverty-fighting community action agencies. This collaboration shows a focus on economic development and broad prosperity will help those living on the economic margins.

Two housing-related techniques arose to the surface of the Open Field discussion. First, many rural tourism economies rely on short-term rentals like Airbnb or VBRO to house visitors. However, these, unfortunately, risk displacing local residents as owners transform leased properties into short-term vacation rentals. The owners of vacation rentals often do not live within the community, so requiring short-term rentals to be owner-occupied, as in Hood River, Oregon, helps ensure that the dollars spent on vacation housing sticks and circulates within the rural community.

A second technique for balancing rural tourism offered during the session was to use land trusts. A land trust is a form of shared land ownership that can protect access to land for local residents and visitors, stabilize local housing markets by keeping rental costs low, and potentially protect against rampant development.

Rural Stewardship Resources

The list below collects additional links, tools, and resources shared during the Open Field.

- The Thrive Rural Field Perspective Brief Stewardship + Equity outlines the history and contemporary situation for rural environmental justice and development and explores new federal policy opportunities for rural communities.

- WealthWorks provides a tested strategy and tools to build sustainable rural economies through value chains that develop local assets and are based on growing eight different forms of community capital, including natural capital. This evaluation tool provides a valuable introduction to the model.

- The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals were shared as a successful, globally implemented framework that seeks to advance economic development and grow and sustain the health of natural systems.

- There is a US EPA program that enlists the help of local colleges or universities for technical assistance and support in underserved communities. A side benefit of working with universities is that it teaches students the value of community engagement and inclusive and collaborative planning processes.

- US EPA has an Environmental Justice listserv that you can join – just send a blank email to: join-epa-ej@lists.epa.gov

- Participants shared how important it is for development planning to include measures of sustainability and stewardship. The Economic Development Administration supports CEDS planning to help a community set balanced development goals.

- Some states have programs that support environmental justice and just transition. One participant shared an effort by the State of Minnesota to put resources back into mining communities called IRRRB.

- Participants elevated access to quality housing as an important component of sustainability. For more on rural housing, visit the Housing Assistance Council for quantitative data, resources and housing advocacy.

- Grounded Solutions Network is the national resource and network for community land trust housing efforts. They have different examples of how to use land trusts in both urban and rural communities.

Join Us! This event was just the first step in a wider conversation – register to attend the next Open Field on June 10 to discuss Rural Environmental Justice.