This is the first in a two-part blog series on principles, ideas, and implementation considerations essential to ensuring that development investments that are part of COVID-19 relief and recovery set the stage for thriving rural communities and a more distributed, inclusive economy.

The COVID-19 crisis is testing America’s resilience. The rapidly accelerating economic fallout makes concrete the risks for a national economy built on the success of just a few key economic centers. When the nation turns to the work of recovery, our goal must be to expand the number and breadth of healthy communities, jump-starting a more equitable and diverse landscape of resilient local and regional economies. The relief funds already allocated and being contemplated by Congress must be designed to enable every community to thrive.

This includes rural and tribal places—and will require a reimagining of the federal policies intended to support them. Early analyses indicate that COVID-19 is disproportionately impacting communities of color, putting health, economic, and racial disparities in America on full display. The virus is now reaching into rural communities and Native American nations where, in many places, the compounding forces of race, poverty, and geographic isolation hits hard. County-level maps are showing an alarming rate per capita in many less densely populated communities throughout the US.

The virus is likely to reach full force in rural places later and receive less fanfare, and the total number of rural cases and deaths may seem small compared to the raw counts in urban centers of the epidemic. Yet COVID-19’s long-term consequences will be no less devastating in an increasingly diverse rural America—and could be worse.

Rural economies were the hardest hit by the 2008 recession and the slowest to recover. By 2017, average rural employment was still two percent lower than in 2007. Businesses were hit especially hard—in the first four years of the recovery, counties under 100,000 lost 17,500 businesses, while economies in counties over one million people added 99,000. COVID-19 will only exacerbate these pressures: the shutdown of commerce has already put small businesses, a key driver of rural economies, into an economic vise grip, and almost twice as many rural areas rely primarily on the recreation industry as urban areas.

In addition, a segment of rural hospitals is unlikely to survive the human and financial stress they are about to encounter. Since 2005, 170 rural hospitals have closed across 36 states, and a recent analysis found 453 more at risk. Already a quarter of rural respondents to a poll conducted in 2019 by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Harvard Chan School of Public Health reported that they were unable to get health care when they needed it, even though 87 percent had health insurance. Losing such a key part of the civic infrastructure threatens not only families’ health and well-being, but poses significant challenges to economic recovery and community development, from the loss of employment to the inability to attract and maintain investment and business.

Any full recovery for the US requires building back better in rural and tribal areas. Crafting policy that aligns with modern rural realities requires overcoming stereotypes, understanding the interdependency of rural and urban areas in creating resilient regions, and a recognition of the diversity of rural America.

While still economically and culturally important, agriculture now employs less than 5 percent of the rural workforce. In fact, across rural America, manufacturing (15%), together with education and health (25%), trade transportation and utilities (20%), and leisure and hospitality (11%), provide over 70 percent of employment.

From vibrant college towns to communities gone bust from the flight of paper mills or coal mines, from hopping cultural tourism locales to centers of furniture, machinery and textile manufacturing, rural America is anything but uniform – and recent analysis suggests that innovation is widespread in rural regions. While consistently older and whiter than the nation as a whole, rural America is increasingly diverse. People of color comprise 21 percent of the rural population and produced 83 percent of its growth between 2000 and 2010, with job-seeking immigrants partially responsible.

Whether rural, urban, suburban, or tribal, geography need not be destiny. But federal relief and recovery packages must recognize the structural nature of the fiscal gap that makes state and local governments vulnerable in times of crisis. They must account for the unique pressures facing Native American nations and rural communities —often far from power centers and with economies linked to the land—as they respond to the challenges of COVID-19 in the midst of adapting to the complexities of a rapidly changing economy.

Doing right by rural will demand more than ‘business as usual’ on the policy front. While the pressures and opportunities faced by rural economies have radically changed, the existing federal architecture for rural policy is old—largely dating to the 1860s, 1930s, and 1960s—and designed for a different time. In addition, many existing programs, funding formulas, program designs, and implementation decisions are crafted in ways that do not work for rural places that face low-population density, limited institutional capacity, geographic isolation and, in some regions, persistent poverty.

In these urgent and challenging times, we should seek to maximize the development return on every federal dollar invested. The following principles reflect the wisdom of rural practitioners from across the country, including the Rural Development Innovation Group, and are informed by successful development practice internationally. We propose them here as a guide to provide policymakers and agencies with direction to maximize development impact in rural and tribal communities:

- Support local ownership and strategies. Rural residents and community leaders have deep knowledge about their communities and what they need to succeed, and they must be the ones to own their transformation. Sovereignty is paramount for Native American nations; rural communities and regions are eager to set their own development strategies and do the work of improving their institutions. Their challenge lies in assembling the right constellation of resources—human, political, and financial—to get there.

- Invest in people and institutions. Funding for people and institutions must accompany investments in physical infrastructure. Very few small towns or rural communities have the extent of capacity available in larger places or cities – planners, financial divisions, grant writers, data and analysts, and the financial resources to contract with experts when they lack the needed capacity in-house. These people and institutions are essential to smart, strategic, and responsible development.

- Increase flexibility and align federal and state funds to meet local needs. The diversity of rural America means that a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to maximize effectiveness. Federal and state funding streams should strive to encourage and support the creation of locally-determined priorities—and then flex and align, as needed, to help bring these locally-determined priorities to fruition. Longer-term investments rather than inconsistent, “projectized” support will provide a better chance for success.

- Measure and reward outcomes. The aim of development is an overall improvement in quality of life. Rather than counting “jobs,” “growth,” and number of services provided, agencies and states should seek to measure outcomes (e.g., improvements in family financial security and health status). Dedicated funding for rigorous analysis in planning and design, and a significant expansion of program evaluation, is badly needed to provide practitioners and policymakers with the data and information to determine what works, what needs adjustment, and how to ensure our public investments maximize the positive impact on people’s lives. Increased transparency about successes and failures is also vital to improve the effectiveness of those investments.

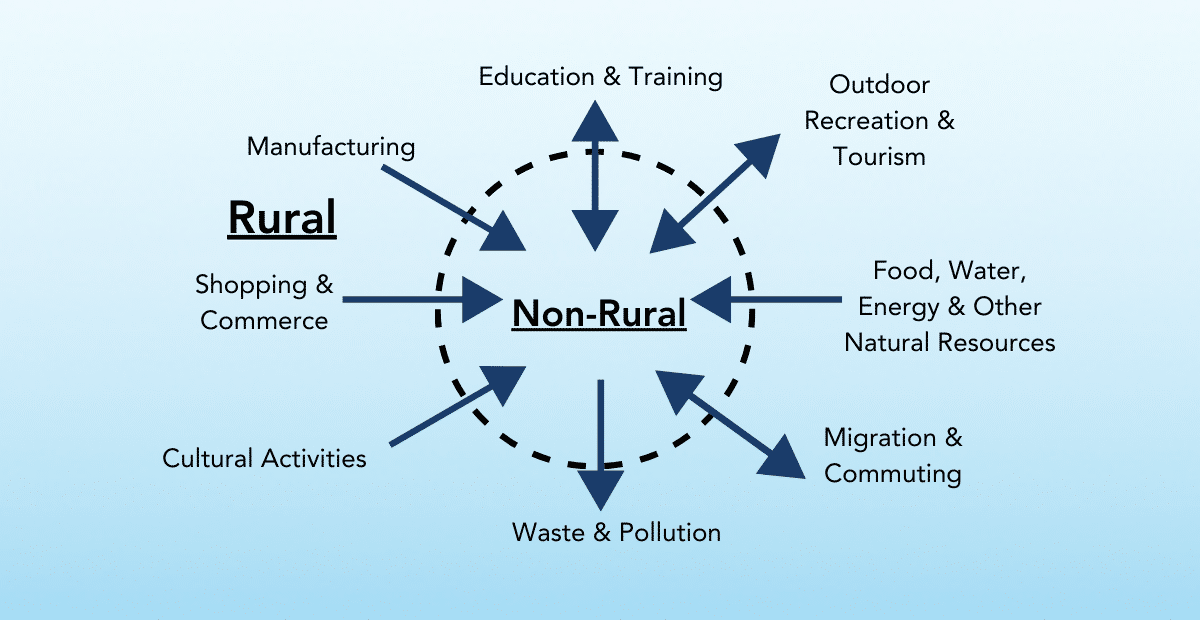

- Embrace a regional mindset. Rural America is staggeringly diverse with economic, historical, demographic, and cultural contexts that differ from one region to another. Both national and local policymakers must be sensitive to regional variation while also considering how individual rural communities exist within a regional economy or system. Urban markets are essential to rural economies, just as rural resources are central to the viability of urban centers. In addition, assembling the critical mass of people, ideas, resources, and connections needed for success requires working across sectors and geographic boundaries in less densely populated places. Smart rural policy requires a regional mindset and a comfort with nuance.

In a less chaotic time, we would recommend a top-to-bottom review of the effectiveness of federal programs, policies, and funding formulas in serving rural regions. This would significantly improve our understanding of the extent to which geographic inequity is built into the current system and the opportunities for improving our impact by modernizing federal policies and assistance. However, with the CARES Act already in law and additional relief packages in the works, we offer these principles as a start.

COVID-19 reminds us that health and the economy are inextricably linked—and brings into extreme relief the perils of a globalized economy concentrated in too few market and corporate centers. This crisis is a vivid demonstration of interconnectedness and shows that what happens to one person, in one place, has a ripple effect. For a national recovery to result in a stronger America, we must reimagine the way in which federal policy helps – rather than hinders – rural communities and tribal nations, making them part of a new economy that is sustainable, equitable, globally competitive, and able to withstand the unknown.

Katharine Ferguson is Associate Director of the Aspen Institute Community Strategies Group and Director of CSG’s Rural and Regional Initiatives. Before joining the Aspen Institute, Katharine served as Chief of Staff for the White House Domestic Policy Council and as Chief of Staff for Rural Development at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Tony Pipa is a senior fellow in the Global Economy and Development Program at the Brookings Institution, where he studies place-based policies to improve social progress in the United States and globally; he has over 25 years of executive experience in the philanthropic and public sectors addressing poverty and advancing inclusive economic development both in the US and abroad.

Natalie Geismar is a project coordinator for the Development Assistance and Governance Initiative in the Global Economy and Development Program at the Brookings Institution.

This blog is also featured on the Brookings Institution website.

Support for this article was provided in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.